The problem with ghost stories is that they, like ghosts themselves, are only barely there. They’re witnessed by one or two people. What is witnessed can take many forms: a feeling, a cold spot in the hallway, a sound from the attic, or a brief vision of the other side. That’s all that we usually get. And that’s enough to make it unsettling, uncanny. It’s enough because it defies the natural order of things.

Ghosts have been with us for a long time. The ghost story is ancient. It borders one of the four grand questions – where to we come from, why are we here, what are we supposed to do, and what happens to us when we die? A ghost is question. It does not belong, it is out of place, it defies the natural order. But a ghost is also a kind of forlorn hope – there is more after we die, even if all that it is is a reminder of a person.

People who claim to study ghosts report that they rarely interact with the living , and if they do, it is most often the briefest of exchanges, a voice on a recording, an orb floating in mid-air, a phone call in the middle of the night on a phone that’s not connected, a light in the darkness. That’s the problem with ghost stories – when all is said and done, a ghost story is told by one or two people about something they claim they experienced briefly and then it was gone. Though writers of fiction can weave a good story about spirits, the stories told by real people about their encounters have very short plots indeed and usually, no conclusions at the end of the telling.

But there are a few stories told by people that have a preponderance of evidence, that were witnessed by many people and were written down at the time, preserved in newspapers and books for the ages to come. Though few, these stories offer us the missing pieces of a ghost story. They offer us plot, characters, setting, and conflict. They do not always offer resolution. Ghost stories are by their very nature unresolved. These few ghost stories with proof are the ones that keep us up at night pondering the nature of things. These rare reports are the ones that haunt us. That’s what this episode is all about.

Not so long ago, around the beginning of the twentieth century, science entertained a strange relationship with the paranormal and especially the work of spiritualists and mediums. Newspapers frequently ran stories about seances and mediums not only performing their wonders in dark parlors but also to sold out crowds in major venues. The religion of spiritualism was in the mainstream. Everyone knew someone who was part of it. Its origin can be traced to the Fox sisters of New York in 1848 when two young girls claimed to communicate with the spirit world through rappings in their small house. If they were telling the truth, it meant that meant one could communicate with the dead. And everyone had someone who had died. It was hope for many of reunion with the beloved, an immediate hope that did not have to wait until their own death. Spiritualism had links to social movements of the age, empowering movements like women’s suffrage and the abolition of slavery. In 1888 the Fox sisters disavowed their prior experiences and told the world that it was, after all, just a hoax. But by then it didn’t matter. The doorway had been opened. The idea of a kind of science of afterlife communication had been established without the need for conventional religion made it too provoking for many to dismiss it.

Today, almost everyone knows what a medium is. A medium will claim that they can speak to, see or hear the dead. They can channel souls who have died and provide a conduit to the living. These mediums are portrayed in movies, on television and you can even go to their place of business and receive a reading. All of this, however, is as nothing compared to a kind of medium that today is all but gone: the physical medium.

Physical mediums at the turn of the century were all the rage. Mostly women, they could speak to the dead, create forms with ectoplasm exuding from orifices in their bodies, and even summon spirits who apparated in front of others, walking about the room and interacting with guests. They could bring a dead person back to the world. Or so they claimed. Countless skeptics arose but countless others witnessed nothing less than the resurrection of the dead. These physical mediums seemed to finally prove that there was no reason to fear death because there was only bodily death. The self, it seemed, went on and they claimed they could prove it. Ghosts were no longer something you randomly encountered on a dark and stormy night. Anyone could meet a ghost if they paid their money and entered the domain of the physical medium. Ghosts could be summoned, spoken to, and even appear in front of your very eyes. For a time, this remarkable phenomenon was all the rage. A dinner at a friend’s house might end, not with a game of cards and some conversation, but with a seance. For awhile, a brush with the world of the dead had become a parlor trick. The Afterlife had become a cheap game.

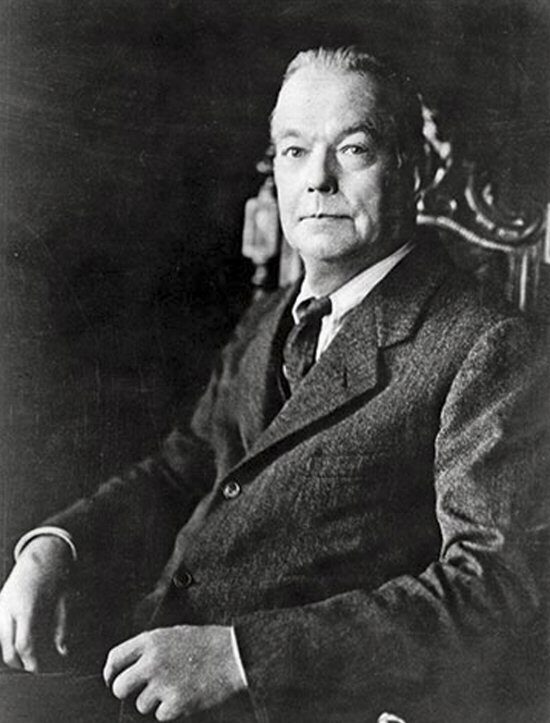

But proof was something that science demanded and at the height of this mania of communing with the dead, there arose a very unique kind of specialist: a person of faith who also had a belief and training in logic and science. People like Harry Houdini, who strove to disprove charlatans and frauds, arose to counter people like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, whose own wife claimed to be a medium and who championed the cause of the physical medium. One such man who would bridge the gap between science and superstition was born in 1863 in a tiny town called Detroit, Maine, just west of Bangor. His name was Walter Franklin Pierce and his story intersects with one of the most famous ghost stories of the twentieth century, that of the Fire Spook of Caledonia Mills in Nova Scotia.

It is a cold winter night in January, 1922. Outside, the wind is howling and the temperature has risen enough for the snow to change to freezing rain. The world is quiet except for the incessant wind, whistling and moaning, and the sound of the storm.

Imagine you are in a small farm house in an out of the way corner of the world, a place so far off the beaten track that you have no running water, no telephone and no electricity. A squatting iron stove is all that stands between you and the usual deep cold that envelops the countryside, and that cold is unforgiving. Oil lamps keep the small rooms lit in the overwhelming darkness of a midwinter night. Your nearest neighbor is a twenty minute walk away, down a road so covered with ice, slush and snow, that it is all but impassable on foot.

It is a dark and stormy night and as the small hours grow and the morning approaches, you abandon the warmth of the bedclothes to arise and begin your day. The first order of business is to start a fire but when you do, you notice something odd. As you force the cobwebs out of your mind, you open the stove door and see that all is cold, not even a spark to kindle a new flame is evident.

But you smell smoke.

Yes, that’s definitely the smell of smoke, closeby, recent, smouldering. You look around for the source, your heart beating a little faster, and you see above your head on the wooden beam just near the stove the clearly charred black line of a fire. Everything stops. Your wife and adopted daughter are still in bed and the animals need to be fed and watered, but all that must all wait. You are Alexander MacDonald, seventy years old, and you must face the fact on that cold January morning that while you slept, your house came incredibly close to burning down to the ground.

Woodstoves can create deadly creosote buildups that line stovepipes and chimneys that will ignite if the fire in the stove burns particularly hot. Of course, that must have been what happened. But by the grace of God, you have avoided a worse fate. After dismantling the stovepipes, cleaning them of the remaining creosote, and checking every seam and connection, you surmise that you should proceed with your day and be thankful. After all, all is well.

It is January 7, 1922 in a small house, far from any main road, in the midst of a clearing in a vast tract of forest in a place called Caledonia Mills, Nova Scotia. Alexander MacDonald, his wife Janet, and their fifteen year old adopted daughter Mary Ellen, were about to be witnesses to one of the strangest set of circumstances ever to come from Atlantic Canada. They are about to be visited by a fire spook, paranormal investigators, and perhaps most frightening of all, the spectre of public opinion. The local Gaelic-speaking folk, though, had another word for it: Bauchans. From the old country, it is said to be a malevolent spirit, a trickster, a harbinger of misfortune. We might think of a poltergeist, a spirit that can interact in the real world with actual physical objects. We might even think of pyrokinesis, the ability to start a fire with a person’s mind. Whatever visited this isolated family in their little farm in the winter of 1922, it proved to be more than the scientific community could easily explain.

The family went about their business for the rest of the day of January 11th, but they would not know another night of rest in that house.

To the average person, the cause of a fire isn’t usually thought to be supernatural in nature. Fires can start for a variety of reasons. Oily rags can heat up over time and spontaneously combust. Improperly ventilated woodstoves can create hotspots. Even an unattended cigar or cigarette can ignite a fearsome blaze. Why the good people of that part of the world settled on ghosts as the explanation says a lot about their background and understanding of the world. There’s a modern bias against country people of a hundred years ago. They are often regarded as simple-minded and superstitious. But these were people who solved problems on a daily basis and who were no more foolish than people are today. Their Celtic background and heritage is not a simple excuse for their belief in bodachs or ghosts. They were not people to lightly label something supernatural. They were well-grounded problem-solvers who understood what caused things to catch and burn. But, as you will see, they were presented with a series of discrepant events, things that simply made no logical sense, then or now. And when something doesn’t make logical sense, perhaps saying the cause is paranormal is merely a logical response, after all. Sometimes, one simply shakes ones head and says, “Might be a ghost…”

Alexander MacDonald kindled a fire in the woodstove he had cleaned that day before he went to bed. It was going to be a cold night. Everything looked fine. He had only been asleep for a few moments when he was awakened by his wife Janet, claiming that she could smell smoke. Alexander rushed into the kitchen and saw flames licking the ceiling just above the stove. He extinguished them with water but decided to stay awake for the rest of the night to make sure the house didn’t burn down. His wife and daughter slept. When they awoke in the morning, they discovered that during the night, Alexander had to put out four more fires in different places in the house.

The next morning, the family made a strong effort to investigate the cause of these fires. They took up all the loose planks that made up the second story of the farmhouse above the kitchen. They wiped everything down, cleaned away all the dust and inspected every inch of wood. They replaced some of the boards, as well. They needed to stay warm and they needed to sleep. They had nowhere else to go. There had to be an explanation. By the end of a grueling day of cleaning, inspecting and replacing wood, they retired to their bedrooms, hoping for rest. But there would be none. Janet awakened Alex at around ten o’clock telling him she smelled smoke again. He jumped out of bed and inspected every corner of the house, but he could find no fire, nor could he smell any smoke. He went back to bed but within the hour the dog’s barking awoke them and when he threw open the bedroom door, he saw an upholstered chair in flames next to the woodstove. Thinking quickly, he opened the front door and grabbed the burning chair, throwing it into the large snowbank just outside the house, where it continued to burn. Alex spent the rest of the night wide awake while the women slept, holding vigil against whatever it was that was starting the fires.

The following two days were fire-free. The family had been through a harrowing experience, but they were beginning to think everything was going to be as it was before, quiet, uneventful, and safe. On Wednesday, however, all hell broke loose. While Alex was tending to the animals in the barn, Janet and Mary Ellen were cooking in the kitchen when they smelled smoke. The stove seemed fine, as did the floor and walls. The ceiling, however, was burning. One of the pine boards was on fire. In those days, the pine boards of the ceiling were not always nailed to the rafters and Janet stood on a chair, reached up and pulled the burning board down, promptly throwing it out into the snowbank next to the charred chair. A few minutes later, another fire started and Alex heard their screaming from the barn. When he entered the house he witnessed a fire in the dining room wall just over the kitchen door – again, high up on the wall. He doused it with a bucket of water. Not long afterward, the wallpaper in the dining room took flame. Extinguishing that, another fire appeared. Soon after, they discovered a pile of old cotton rags burning upstairs. Dousing that, they went back downstairs only to find another fire had begun, this time in the tiny bedroom off the kitchen. It was too much to handle. Something was wrong, something they could not understand. And the night was getting colder.

At his wits end, Alex MacDonald told his wife and daughter to go to the nearest neighbor, the MacGillivrays, about a kilometer down the road. “Get help,” he told them. In the freezing rain, the two women struggled through the slush and snow, Mary Ellen far outpacing her old mother’s progress. Walking in deep slush is grueling and slow. Mary Ellen arrived first and told the neighbors that their house was on fire.

Leo MacGillivray and his brother-in-law, Duncan MacDonald, responded by hurrying to the MacDonalds house, but only after hitching their horse to the wagon, leaving Janet and Mary Ellen to make their way back to their home on their own. Meanwhile, all alone in the house, Alex had spent his time there putting out the flames that seemed to arise all over for no particular reason. When the neighbors got to the MacDonald home, Alex asked them to stay inside and watch for fires while he went outside to see to his wife and daughter. MacGillivray’s brother-in-law searched the house – there was no fire burning anywhere. Janet, Mary Ellen and Alex rejoined them inside. The entire flight and return had taken forty-five minutes.

Relieved, Janet recovered enough to light a fire in a smaller stove to heat water for tea. Seated around the kitchen and discussing the events of the night, they noticed the dog’s hair standing on end as he began to growl. What happens next is stranger still.

According to reports, a bright white light silently filled the little house, moving from the end of the parlor to the other end of the house. Leo MacDonald, the brother-in-Law of the neighbor, had worked for an electrical company and described the scene as looking and smelling like a short-circuit of a high-tension wire, but much brighter. As it moved, it set parts of the house aflame.

And the fires began again. The bedclothes, the dining room wallpaper, another fire upstairs in a pile of rags. Then a bright light from the parlor brought them to a burning sofa cushion. Things that were already wet began to burn: paper, wallpaper, rags, all soaked, began to burn. A cardboard box, an empty pillowcase, a small cotton table napkin. What is strange is the presence of cotton in or on places and things that were burning. The fabric the witnesses saw was mostly white with occasional colors. If it was a paranormal occurrence, surely a ghost wouldn’t need cotton to start a fire? Other neighbors arrived, and there were many who saw a fire spontaneously begin. No one there knew how these conflagrations began. Most of the time, it was easy to put the fires out. No one could fathom why anyone would want to set these fires, not to mention how. By suppertime, everyone involved had put out thirty-eight separate fires.

The MacDonalds made a decision. They could no longer live in their own house. With the help of their neighbors, they gathered their possessions and moved in with the McGillivrays.

As they were packing, Michael MacGillivray and John Kenny approached the home at around ten o’clock in the morning. They had heard about the strange fires and were about ten meters away when they say they witnessed a bare forearm and hand extend out from a window on the northeast side of the house, waving a white piece of cotton in the air from what appeared to be the parlor. Running into the house, they asked if anyone was in the parlor just now, but it was clear to all that no one was – they were all busy gathering their possessions and readying to leave. Inspecting the window in question, it was shut and frost-free.

The MacDonalds moved into their neighbor’s house. Alexander had livestock and a barn to tend to, so he spent each day next to the house. Every day when he walked the road back to his home, he fully expected to see it burned to ashes, but every day after his family had moved out he found the house untouched and whole. Once they moved out, it seemed, the lighting of the fires ceased.

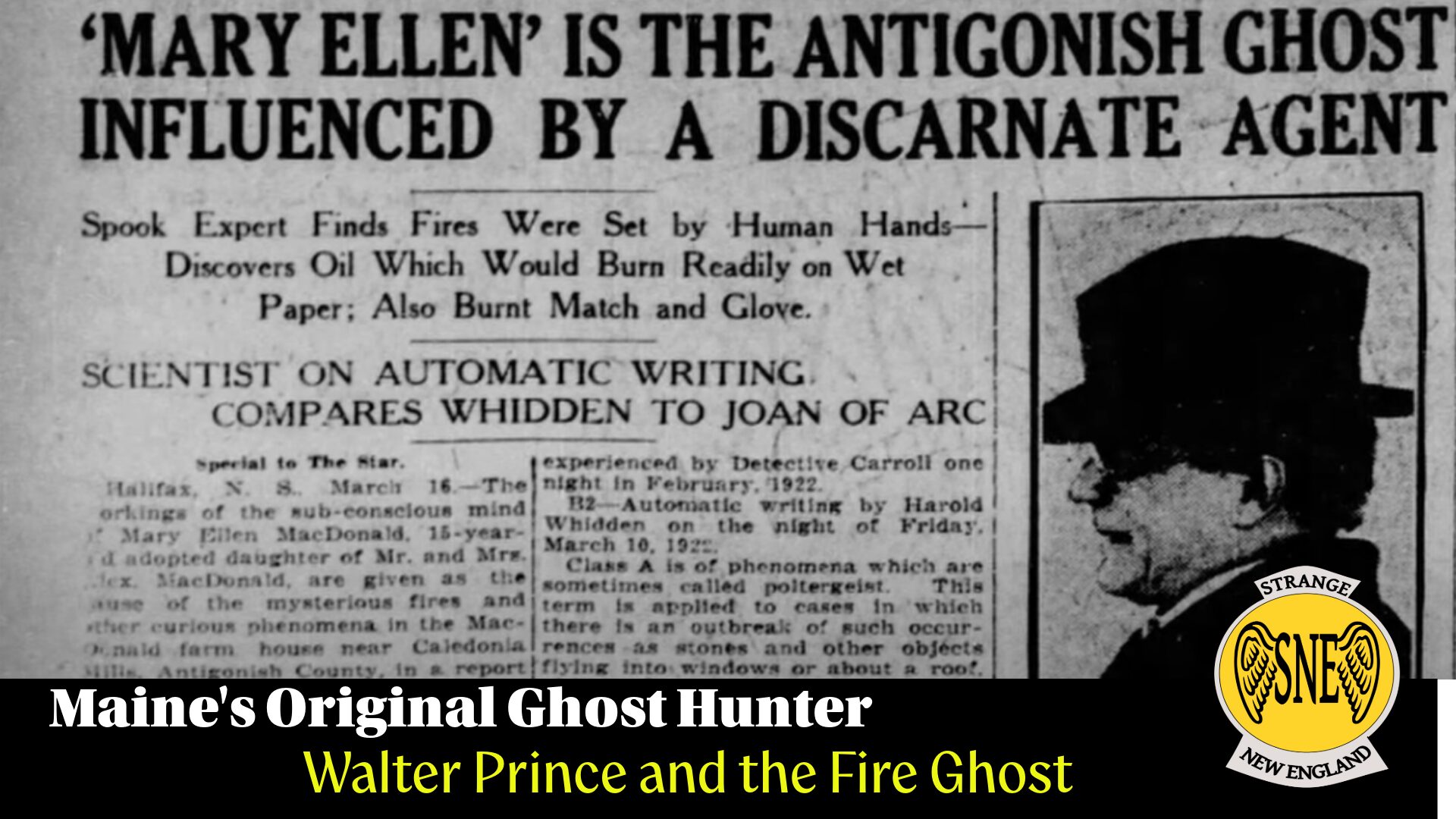

On January 16, Harold B. Whitten of Antigonish heard of the story and decided it was newsworthy of the front page of the local paper. Whitten was the local correspondent for the Halifax Herald newspaper and on January 19, the first Herald story on the Fire Spook of Antigonish was published. The world has just been alerted to the story and it would most certainly respond.

Whitten was dispatched by his editor to visit “the mystery house” and see for himself what had transpired. Getting there was difficult. Using a horse drawn sleigh, Whitten and a friend lost the road but followed a track until they made it to a nearby farm. Leaving their horse and sleigh there, they trekked to the house on foot. What they discovered confounded them. Besides the partially charred furniture in the snowbank outside the front door, they found a very small house, whose inside they described as a ‘sorry-looking spectacle.’ Charred ceiling beams, scorched parlor window, bits of burned wallpaper and dark marks on the floors. The floor plan was simple. The front door opened into the 14 by 12 kitchen dominated by the woodstove. The dining room was adjacent and was small, only 6 by 10, and it, too had a small stove. A small 6 by 6 bedroom was to the left of the dining room and beyond the dining room was the 14 by 17 parlor, the largest room in the house. As they walked through, the reporter and his friend tried to imagine how any person could have wound their way through and past six other people who were fighting the fires only to start other fires behind their backs. Whidden wrote, “We could not see how anyone could have started [the fires] under the circumstances…taking into account the way the house was laid off, its smallness, and the very fact that there was always someone in the house when the fires broke out. No one could offer an explanation, and the case remains a mystery.” After having a chance to interview the MacDonald family, he concluded that they were trustworthy, if overtired. They were dealing with gossip from the neighbors, the loss of a home of their own, and the anxiety of not understanding what had happened to them or why. Alex MacDonald told Whidden that he was abandoning the house and planned on building a new one closer to the main road. Whidden took copious notes and interviewed as many local folk as he could. Upon his return to Antigonish, he prepared the story for the Herald. He wrote, “I wrote the facts given to me. The case was so mysterious, and the circumstances were so weird, that I felt my position was unenviable. Therefore, both care and caution had to be exercised to write an accurate and straightforward story. There was not one word of exaggeration in it.”

And so the media fire started. The locals blamed spirits, ghosts, probably because it seemed impossible to not have seen a living person setting the fires. However, locals also knew that alcohol, which would have been readily available in most rural homes, burns with a blue flame and it appears clear, like water. People who were dubious of the ghostly explanation wondered why a ghost would need cotton to kindle flames. That would seem to indicate that a person, a human, was responsible for the fires, but why would anyone in the small family want to burn down the only home they had? Once the story hit the press, countless theories abounded, most of them supernatural in nature. It seems that the house was not the only thing set aflame – the imagination of countless people was, as well. One reader suggested vampirism, another offered chemical reactions from the natural environment as the cause – phosphorus. Methane might be the culprit, seeping up into the house from the coal-laden ground of the area. Of course, the Devil himself was also blamed.

Other parts of the story also begin to be told, parts that happened before the fire starting. In March of 1921, it was said that Alex went to his cow barn and discovered that the cows had escaped from their stanchions, something that would be very difficult for them to do. After fixing their stanchions, the cows got loose again the next morning. Alex fixed them again but in the time it took to go back into the house and then out again, the cows were loose again. Something this mundane would hardly seem remarkable, but in the world of early 20th century Nova Scotia, word traveled fast and even the slightest, strangest aberration from the norm became part of the local zeitgeist. The reason the cows escaped, according to the locals? bauchans, or ghosts.

Later in that same month when the cows kept escaping, the family was visited by their son-in-law William Quirk, who was married to their natural daughter, Mary. With friends, William was cutting fence posts near his in-laws’ home and decided to pay them a visit. They found Janet at home with Ellen. Alex was attending some business in Antigonish and wasn’t expected back before nightfall. After dinner, young Ellen took her brother-in-law out to the barn to check on the cows and she commented to him that the neighbors didn’t like her parents. When asked why she thought this, Ellen explained that someone was untying the cows and setting them free. It must be a neighbor, she said.

On their way home, William Quirk witnessed a riderless horse pass by them on the main road. Such a sight is seldom seen. The horse passed them and headed towards the MacDonald homestead. Looking behind them, they saw a man walking away from the homestead, a man they should have encountered already as they made their way down the road. A few days later, according to Richard Carroll, an early investigator of the case, they returned to the area and asked around, but of course, no one had seen the man and there were no footprints. The cows were continually released from their stanchions in the barn for the next two weeks.

Another such tale speaks of neighbors who were cutting hay near the farm and watched as the roof of the MacDonald house began to burn into a conflagration. Dropping their scythes and running to aid, they ran into a hollow on their way to the farm, temporarily hiding the house from their view. When they reached a rise and saw the home again, all was well, no fire, flames or smoke. A forerunner? Or was it simply the bright red sun setting low in the sky, just above the roof of the MacDonald home? To add to this atmosphere of mystery, an unnamed man claimed to hear chains rattling from the barn as he passed by on his way home in the early evening. A blue glowing light within caused him to rush to the door of the barn, obviously to help the owner save his livestock from a fire. But as he opened the door, the interior was dark and still. Obviously the truth of these events seems questionable – stories take on a life of their own – and are more likely the result of a good storyteller adding suspense and intrigue to the events that eventually unfolded into something the newspapers seized upon as newsworthy. Everyone loves a good spook story, right?

The editor of the Halifax Herald, William Dennis, knew a good story when he saw one. He published the tale and asked people to submit possible explanations for the strange phenomena. Some people postulated it was methane gas coming from the coal deposits below. Some people claimed it was the powerful radio signals passing through Caledonia Mills between the radio towers at Wellfleet, Massachusetts and Glace Bay, Nova Scotia. Most people seemed to believe in spirits.

This story sold papers and was reprinted in other papers across the world, not just Canada. Dennis was determined to breathe as much life into this story as he could and one way to do that was to hire a professional investigator to visit, investigate and report his findings back to the reading public. He found that investigator in a character of local color named Peachie Carroll.

Peter Owen “Peachie” Carroll from Pictou, was a former police chief and member of the provincial police. He was trusted by law-abiding folk and feared by criminals and had a history of always finishing what he started. Peachie Caroll made his way to Antigonish, interviewed many, and then journeyed the hard miles to the MacDonald home. Accompanying him was the reporter who started the media rush, Harold Whidden. Together, they took enough supplies with them for a week, including a new sheet-metal stove which they promptly installed upon arriving in the now abandoned home.

The February 14th issue of the Herald reported a strange occurrence around midnight. Peachie Caroll tilted his head intently while he listened to the unmistakable sound of footsteps on the second floor planks above his head. He arose quietly but his action awoke Whidden who asked, “Did you hear that?” Carroll put his finger to his lips and nodded yes, pointing upwards. They listened as the footsteps came down the stairs, entered into the parlor and….stopped. This whole episode lasted six long minutes. When they entered the parlor, it was empty. They thoroughly searched the house, but again, nothing was to be found. Fearing that the cold was too intense to allow them to remain in that house, they packed their things and returned to Antigonish. Once there, Peachie Carroll wrote, “After spending two days and two nights in the house, I firmly believe that neither the fires nor the strange happenings were the work of human hands. These people (the MacDonalds) are just as innocent of this affair as I am myself. If anyone dares to point the finger of accusation at any one of them in this matter, I hope they would be made to prove it legally or swallow their words.” Whidden and Carroll concluded their article with a notice of a two hundred dollar award to anyone who could prove them wrong within a year.

This was a time ripe with psychics. Spiritualism was in full bloom with physical mediums filling concert halls and spirit mediums filling their parlors night after night with what they called proof of another realm, the realm of spirits and the dead and through their ministries, the living might contact the spirits. Led by none other than Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, both sides of the Atlantic were abuzz with supposed communications from the spirit realm. To the true believers, the MacDonald farm and the strange occurrences there were proof that such things existed. Peachie Carroll’s report and vague conclusions were published in many major American and British newspapers. One article caught the attention of a man who had spent much of his life developing a reputation for honesty and trustworthiness, a skeptic and revealer of frauds in the psychic and spiritualist communities: Walter Franklin Prince. When Prince offered to investigate the Antigonish Fire Spook free of charge, Halifax Herald’s owner couldn’t refuse.

Today we would call Dr. Walter Franklin Prince a parapsychologist. Indeed, he has been referred to as one the great masters in the field of parapsychology, but in his time, that term did not yet exist. He was an interesting blend of faith and reason whose interests led him to study the claims of people that others might easily dismiss.

Prince had originally been a clergyman and he likely began his ministry and call to the church in Maine. Graduating from Maine Wesleyan Seminary in 1881 he became a Methodist Episcopal minister early in his career, he received a Bachelor of Arts and a Bachelor of Divinity degree from Drew Theological Seminary in 1896. He continued his studies at Yale as a graduate student and in 1899 completed his Ph.D. at Yale, focusing on the science of psychology. His focus was on what today we would call multiple personality disorder, or dissociative disorders, something very new to the science. In 1910 he became the director of All Saints Church in Pittsburgh and then the director of psychotherapeutics at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in New York City in 1916. Psychotherapeutics was an early form of talking therapy [psysvhotherapy] and at the time it was this link between religion and science that made him well-suited for his job. It was during his time in New York City that Prince met people he never would help change the direction of his career. A believer in science but also in things he could not yet prove, he sought out people who could help him understand precognition, telepathy and clairvoyance, all abilities he believed to be real. However, he was highly skeptical of physical mediums, the great paranormal showmen of the day, and he would use his considerable gravitas to disprove. In 1915 he left his position at St. Marks to work at the American Society for Psychical Research (ASPR) and became the personal assistant to its director, James H. Hyslop. Now his work was focused on disproving parts of the psychic world and proving others parts. He made it his business to learn the sleight of hand, the tricks, and the mechanisms by which physical mediums fooled the public, traveling far and wide to investigate as many cases as he could. He became a friend to Harry Houdini and others whose work was to disprove physical mediumship. Unlike Houdini, though, Prince accepted some psychic phenomena as real, if not yet explainable.

You see, there was another side to William Franklin Prince. In his book, The Psychic in the House, Prince describes one of the first cases of multiple personality disorders in scientific literature, that of “Theodosia,” who really was his adopted daughter, Doris. Having met Doris in his work as a minister, he and his wife took her in and then, he chronicled his work with her and all of her other selves. He claims in that book that the young woman was not possessed by spirits but had developed separate personalities during various points in her life. He describes her separate, other personalities as having some latent psychic abilities such as clairvoyance, seeing people who weren’t there, and hearing rappings and other physical manifestations that he could not explain. Still, he explains that he was able to help her gain back her true self and only one other personality remained, someone called Sleeping Margaret who he was able to speak with while Doris (Theodosia) slept. Otherwise, her psychic abilities vanished and she was made whole again thanks to his counseling and therapy. This book, among others, helped raise his prestige and place him among the intelligentsia of his time. It provided a clear, scientific picture of a patient with a strange, but identifiable disorder, and one that could be managed with professional help. What is important to remember about this book is that it was published in 1926, four years AFTER the events he would encounter in Calendonia Mills, where he would meet another adopted daughter whose life he would not save. In fact, the actions and findings of Prince may have done quite the opposite.His study of his own adopted daughter would have ramifications for young Mary Ellen MacDonald and his assessment of the Caledonia Mills Fire Spook.

The February 26 Boston newspaper entry reads: “Halifax, N.S. Feb 26. – A party of inquisitive scientists now threatens to break in upon the quiet of the Antigonish ghost, whose fame grows with each new fire he, or it, causes. The exclusive wraith will make the acquaintance of a small group of quite distinguished men if plans being discussed today are carried out. Dr. Walter Franklin Prince, Director of the American Institute for Scientific Research, New York, has declared his intention of calling at the haunted house if he can arrange a leave of absence. If the American makes the trip he will be accompanied by a member of the Montreal Spiritualists Society and a professor of science from one of the maritime province universities, it was announced today. The Antigonish ghost has become quite an international affair since it was first heard of a few weeks ago. The haunted house is the home of Alexander MacDonald, near Caledonia Mills, in a little-inhabited valley deep in the mountains and woods. Mr. MacDonald, his wife and their adopted daughter fled the place in terror in the dead of winter with weird tales of ghostly tampering with cattle and a series of unexplainable fires. The tale obtained wide credence and the provincial police sent a detective. He was accompanied by a newspaperman, the two taking up their residence in the MacDonald house for three nights, fleeing it finally with an eerie tale of being slapped in the night by hands that didn’t seem to be attached to anything in particular. Now comes the call for scientific investigation.”

For his part, given that he was paying for nothing but also receiving no recompense for his investigative work, Prince promised the editor of the Herald that regardless of public opinion, he would report his unbiased findings and the reasons for them in his paper. Prince publicly vowed to be objective, but it is clear in retrospect that he went into the investigation with some preconceived notions. He wasn’t even trying to hide his bias when he told friends and reporters that he suspected the case had something in common with the famous Amherst Poltergeist case of 1878-79. In that case, fires, moving furniture and items flying through the air were reported. Prince, a theologian who tended to use scientific as well as psychic explanations for strange phenomena, believed that a young relative of the family in question, Esther Cox, suffered from multiple personalities and one of them committed the acts in the household. In fact, Prince may have had an ulterior motive in mind when he decided to investigate the fire spook of Caledonia Mills. Was he formulating a theory on poltergeists or indeed, any psychic phenomena and its possible connection with the human psyche and its ability to somehow generate other personalities.

Prince arrived in Halifax on March 4, 1922, taking a train to Antigonish on March 6th. During this time, he interviewed as many people as he could find who had some knowledge of the happenings at MacDonald’s farm. He learned of household items and expensive farm equipment going missing. Animals secure in the barn had been escaping with no one around to release them. He learned that a total of thirty-eight fires had been fought in one night in that little place. He discovered from the locals that Alexander’s idle younger brother had been kicked out of the house for drunkenness and foul behavior and he had shouted a curse to the family. The locals deferred to the explanation of spirits.

Another story from twenty years prior emerged for Prince to consider, although he would assign it no weight. In that tale, Janet’s mother had been taken in by the couple after being placed in a facility called the County Home for the Insane and Destitute, or known to locals as the Poor House, by her siblings. Unable to live alone anymore at 87 years of age, Mary Boyd Cameron had developed dementia and was difficult to deal with. Janet could not live knowing her poor mother was consigned to the Poor House and Alex agreed that his mother-in-law could live with them instead. It was a fateful decision. In those days, treatment for elderly people suffering from dementia was not well-developed or understood. Today there are therapies, special facilities and people trained to assist patients with dementia so they can live as comfortably as possible. Janet had no idea how to deal with her mother who was wandering all hours of the day and night, refused to eat, and did not know who she was. As the weeks grew into months in that small house, the walls began to close in. In the Poor House, at least there was round the clock care for patients. Here, Janet was assigned with all the care, morning, noon and night and it began to wear on her. She feared for her mother’s safety and health but word spread that she had to tie her mother into bed to keep her safe, and eventually she had to nail her door shut to stop the woman from escaping so she and her family could get some rest. It must have been a trial for the family, a horrific ordeal. Locals told Prince that one night, at the end of her rope, Janet reportedly shouted to her mother, “I hope the Devil in hell comes and takes you before morning!” At that very moment, the locals claimed, a black dog appeared in the house and walked from the kitchen into her mother’s room. Stunned, the MacDonalds went into the room, but the black dog had disappeared. To the Celtic peoples of Antigonish, this was a forerunner, a messenger from beyond, the Cu Sidhe (coo-shee), a hound who guides the soul after death. Of course, this would indicate supernatural occurrances had taken place in the old house prior to the fires being set. Walter Prince paid this no heed. Mere hearsay. But such a detail helped keep the story and its supernatural origin alive. Even if there had been no black dog, the idea that a woman would wish her own mother would go to Hell was a stunning revelation. Perhaps Mrs. Cameron was back, with the flames of Hell licking at the wall paper and boards of the MacDonald home.

Prince was fifty-nine years old and could well be considered a psychic detective, a kind of Sherlock Holmes. He was a fellow who laughed at his own jokes, sure of himself, and also sure that ghosts and things that go bump in the night were not usually the cause of unexplained events. He wasn’t easily spooked. Gathering all the supplies he would need for the few days he would spend at the house, on Tuesday, March 7th, with a few people accompanying him including the original reporter, Harold Whitten, he set off for the little house in Caledonia Mills. He also had persuaded the MacDonald’s adopted daughter Mary Ellen to accompany them back to her home to be present while he investigated.

When he got there, he set various traps, unbeknownst to the others, to catch the perpetrator of the fires. He had even brought a revolver with him and sat up all one night in the parlor with it on his lap, waiting, like Doctor Watson in some Sherlockian reveal. He also had a camera and a magnesium flash next to him to light up the darkness all of a sudden, if need be. He was ready.

But nothing happened. No fires. No unexplained phenomena. Eleven days after he arrived in Canada, he left to return to New York. He would publish his findings in the Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, but he gave his reasons to the editor of the Halifax Herald, as agreed. His findings were logical. Most of the fires or residue of fires in the house outside the reach of someone who was five feet tall. Ghosts have no set height. They presumably can fly, or at least rise. In the cases where there were fires higher than five feet tall, small pieces of cotton were always found adjacent to the burn. Why would a spirit require cotton to start a fire? Finally, he claims that there were no fires that occurred where the daughter, Mary Ellen, could not have been a few moments earlier. She could have also set free the animals in the barn and been responsible for the missing items in the household. There was no doubt about it, he claimed: Mary Ellen MacDonald was the culprit. She was the firestarter.

But it didn’t end there. Prince took it upon himself to claim that perhaps she was suffering from multiple personalities and that one of her personalities took over to set the fires. This would line up with his current theories of mind which he would, four years later, publish in his book, A Psychic in the House, where he claims the same cause for his own adopted daughter’s strange behavior. He claimed that Mary Ellen was simple, with the mind of a six-year old. She was unsophisticated, not possessed of any intelligence greater than that of a child. Because of that, he thinks here may be been another personality, an older, more sophisticated one, somewhere within. Or, he determines, if that is not the case, perhaps she was possessed by a ‘discarnate’ agency. He leaves which discarnate agency to the mind of the reader. He sums up his findings as follows:

“The fires were set by human hands, but almost certainly without guilt, probably in an altered state of consciousness and possibly influenced by a discarnate agency …though not yet probably, transcends the purely psychological, and if so, would be in harmony with the suggestion that the girl was temporarily obsessed. I have, as yet, no convictions on the last point one way or the other, but I am glad to add this case to the data under consideration.”

He left in a whirlwind, just like he arrived. He had a bright future. Not so for the afflicted family, now forced from their home. The MacDonalds all moved in with the Quirk’s, their natural daughter, in Roman Valley. The father was the first to die, in March 1923 from pneumonia. Janet lived on with her daughter until she died of old age in September of 1932.

Mary Ellen, however, had a slightly more complicated existence after the events at Caledonia Mills. Prince blamed her for setting the fires, but he offered no concrete proof that she was the culprit. It was all circumstantial. He claimed she had the mind of a child and was possibly possessed or at least dominated by another personality within. Peachy Carroll, the policeman who had initially investigated the fires, fought back against Prince’s assessment of Mary Ellen. “For the chances she had, she is real bright,” he wrote. The local population was also displeased with Prince’s findings. He was, after all, an outsider and an aesthete, someone who claimed superior knowledge and insight. Yet he provided nothing but circumstantial evidence, including a bottle of turpentine he claimed to have discovered while staying at the MacDonald House, even though many people had searched the small home before Prince. It looked like a dubious discovery to everyone except Prince. Did he conveniently ‘find’ the turpentine, the supposed accelerant, that soaked small pieces of cotton before they were lit by Mary Ellen? And what of the glowing ball of lightning seen by five people at once, as it floated through the house? Prince does not say.

In October of the same year, 1922, Mary Ellen was arrested for trying to burn down a barn. Within weeks she was admitted to the Provincial Hospital for the Insane of Nova Scotia at Dartmouth. She was sixteen years old. Her parents refused to speak of her arrest. She remained in the hospital until 1926, when she was released. She found work as a dishwasher at the Frisco Cafe in Halifax and lived as a boarder with the Fenerty family. Twenty years old, living on her own in a big city after four years in an asylum, suffice it to say, she did not have an easy lot in life. Within a year she was arrested when she was found partially dressed in the bed of a Chinese laundry worker, possibly using opium. The charge was vagrancy, which meant night-walking or prostitution. She spend six months in the Halifax City Prison. It was noted at her trial that she was the girl involved in the Caledonia Mills Fire Spook incident. After she was released, she showed up in northern Ontario. By the 1960s she was calling herself Helen McGuire, having shed herself of the persona from Nova Scotia. She ran a small shop and boarding home though rumors persisted in Nova Scotia that her boarding home was a front for a bootlegging operation called the “Bucket of Blood”. She married a man named Austin McGuire who had been a boarder of hers, and they had a daughter, Theresa. Eventually, she moved to Sudbury and grew old in place, eventually dying in a nursing home on June 8, 1987.

There is no doubt that Mary Ellen is probably the firestarter in Caledonia Mills. The house remained standing, unburnt, for many years to come and many inquisitive people visited the ruin. It was the local haunt, the famous place whose mysteries were never actually solved and whose fame continued to grow. Some people claim that the family haunts the location of the house, now gone, to this very day.

Be that as it may, there is a story here of cruelty and pain. In all likelihood, a sixteen year old young woman was driven to set fires in her adopted home for no reason known to us. Fires began only when she was present or directly after she left. No fires started after her absence. She used cotton to soak up an accelerant, probably alcohol which burns with a cool, blue flame. How she lit these things with no one noticing is not known. Why she did it is also unknown.

Mental illness is normalized today – we’re aware of it and hopefully treat it as we would any physical illness. But in 1922 it was stigmatized. Young Mary Ellen was uneducated, adopted by very old people, and isolated in a very rural part of the world with no peers and hardly anyone else to interact with. With Prince’s accusation there for all ther world to see, her own small world got even smaller. There was nowhere she could go in Nova Scotia to forget that she had been accused of setting the fires in Caledonia Mills. Walter Prince did not treat her kindly with his words and her life’s trajectory was severely affected by his findings.

For his part, Walter Franklin Prince enjoyed a meteoric rise in his fortunes. His publication of the book, “A Psychic in the House” cemented his reputation as a man of science (with obvious modern failings) and he would take his place alongside Harry Houdini in the Scientific American’s panel that examined and reported on paranormal claims. He continued to expose mediums, all the while still believing that some of what they claimed was real. He was the only American except for William James, to become President of the Society for Psychical Research in London from 1930 to 1931, surely a very high achievement indeed for a farm boy from Detroit, Maine. His life seems the antithesis of Mary Ellen’s life.

No more fires were ever reported in Caledonia Mills after the MacDonald family moved out. Walter Prince seemed to have the very last word on the subject. But there are some fires that cannot be put out.Prince, an early therapist, did nothing to help Mary Ellen even though some look upon him as a pioneering psychotherapist. It can be asserted that he treated her unkindly, probably to find yet another example of a hysterical woman who was under the control of her unconscious, consigning her to a life weighed down by his judgement.There is no evidence that he ever showed an ounce of thoughtfulness or care toward Mary Ellen and indeed, it can be asserted that he used her to further his own research and investigations to build his own theories and publish his own work four years later. It can be argued that Mary Ellen’s life was destroyed by these events and instead of helping a mentally ill child, left the province as quickly as he came, made an assessment that offered no hard evidence to support it, and profited from his investigation of the Fire Spook of Caledonia Mills.

But in the end, it has to be said that if she was the firestarter, she must have been very busy indeed. If she had the mind of a six-year old, as Prince asserted, would she have been intelligent enough to outwit her parents, the neighbors, Constable Peachy Carroll, and Harold Whidden? Would she have had the foresight, planning ability, not to mention the stealth, to fool every single person who investigated, except for the man from away, the outsider, who must, after all, be smarter than all the locals? Hardly.

Imagine leaving small, lit pieces of cotton burning and then going to bed, not knowing if the house would burn down around you? Would she do such a thing? Could she? Possibly. The only thing left of the MacDonald home in Caledonia Mills today is the memory of events that happened in 1922 and unanswered questions.

REFERENCES

Prince, Walter F.,”An Investigation of Poltergesit and Other Phenomena Near Antigonish”. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, v.16, 1922.

https://archive.org/stream/aspr_journal_v16_1922/aspr_journal_v16_1922_djvu.txt

Graham, Monica, Fire Spook, Nimbus Publishing Limited, Halifax, NS, Canada, Copyright 2013.

A look back at the mysterious haunting of an Antigonish County farm, 100 years later | CBC News

TimesMachine: February 26, 1922 – https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1922/02/26/issue.htmlmes.com