Not everyone can claim that they were born in Purgatory, but Andrew Tozier could, on February 11, 1838. Purgatory is a town near the Monmouth-Litchfield line in central Maine and is neither a heaven or a hell – like most towns, just somewhere in between. But during his life, Andrew Tozier would see more than his fair share of the landscape bordering Hell, even if it was all man-made. In fact, he would become one of the most interesting and least noted figures of the American Civil War.

Tozier’s family moved from Purgatory to the Plymouth, Maine area in 1848 when he was a mere ten years old. His father, was an abusive alcoholic who wrought his anger upon his children. We do not know exactly at what age Andrew ran away from home, but it is likely he was quite young. The fifth of seven children, his absence meant one less mouth to feed at the Tozier homestead, but it also meant that young Andrew was now penniless, and on his own in a largely agrarian state, with no real prospects and no plan for the future.

In that, he wasn’t alone. In the 1850s before the advent of the American Civil War, there were large numbers of ‘homeless’ men moving from place to place in search of work, food, and warmth in the winter. Tozier likely took a common route – he may have made his way to the coast and became a sailor. He may have been a day laborer or worked from season to season, depending on the harvest. He may have found work in the lumber trade. Whatever he did, he was surely uneducated beyond a basic grammar school experience and he was certainly a wanderer, growing up rather quickly on his own, away from any home.

We do know that he reconnected with the Tozier clan in 1861 when he returned to their Plymouth home. Lincoln had called the banners and it was time for twenty-seven year old Andrew Tozier to settle into a trade, of sorts. He signed up to fight for the Union, enlisting in Company F of the 2nd Maine Infantry. In those days, local groups of men could form units and fight together within the larger companies in the army.So it was in Maine, like it was everywhere else. Andrew would have received the basic training and drill that any of the soldiers of the newly formed Army would have received. In the early days of the war, the number of battles were few and far between, but the 2nd Maine saw action in one of the early ones. Andrew Tozier was in the thick of the Battle of Gaines Mill, also known as the Battle of Chickahominy River. In Hanover County, Virginia, on June 27,1862, General Lee made the largest advance of the confederate side thus far in the war, pushing the Union troops back over the Chickahominy River in retreat. Tozier was wounded in the battle almost a year to his date of enlistment, losing his middle finger to a minie ball, breaking one rib, and receiving what must have been a lifelong ailment for him – a bullet in his left ankle that went in but never came out. Captured as a prisoner of war by the South, he recuperated in two different Confederate prisons in Richmond. He was used to hard living and managed to heal while incarcerated. He was eventually paroled and allowed to return to the north, this time with Company I of the 20th Maine.

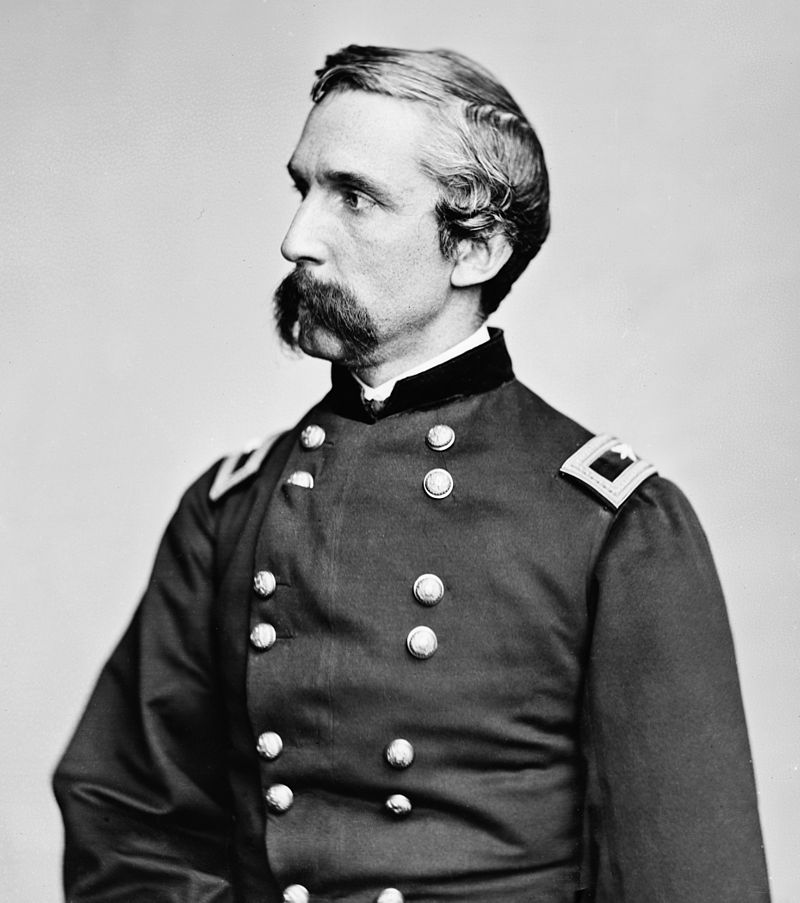

In the early part of the war, nearly every soldier was inexperienced. A soldier like Tozier, already wounded, imprisoned, battle-scarred and now back to fight again, would likely have had some gravitas with the newer recruits as someone with at least a modicum of knowledge of how to fight.His experience in battle, brief though it was, set him apart from the rest of the men. It must have been an odd thing for him to experience – the respect and admiration of other soldiers for an ill-educated rambler from central Maine. The whole unit was a little like him -it was made up of men from other units, leftovers, remnants and the odd new recruit. That’s how Tozier got in to the 20th Maine. Their leader was a scholar, an unlikely military strategist who knew his martial training from reading ancient texts in Greek and Latin. Andrew Tozier didn’t know Joshua Chmaberlain, not then. He was his commander and that was all he needed to know. Like all of the men in the 20th Maine, he knew how to work, how to walk, how to make do. It was something that had kept him going when everything seemed like it was going against him. He had been wounded and captured, but here he was, back in the midst of the action. Events would conspiure so that in less than a month when another soldier’s drunkenness reared its ugly head, it gave him the opportunity that changed his life forever.

To be a bearer of the colors for a unit was an honor among the soldiers of the day. It was generally believed by the soldiers than the man bearing the colors was the bravest of them all. He was in the front. He was bold. A color bearer led the men into battle and gave the soldiers a focal point on the field when the fighting started and the fog of battle descended on them. A soldier looked to the color bearer and followed him – no other real communication was possible on the field once the guns began to fire. Hiram Maxim, another Mainer from Sangerville, had not yet invented smokeless gunpowder and in the heat of any Civil War battle, soldiers were often limited to being able to see only a few feet in front of themselves. The color bearer might be the only sight recognized in that field, once the bullets began to fly.

Sergeant Charles Proctor was the color bearer for the 20th Maine as it marched towards Gettysburg. Imbibing too much liquor one night, Proctor became so riled up and intoxicated that he began to cuss out the officers of the regiment. Acknowledging that he was not in his right mind because of drink, the officers limited their response to him by taking the colors away from him, one of the greatest of insults one could give to a soldier. There was no time to let him sober up as they marched onward to battle. Three recruits in the rear tried to frog-walk him for awhile as they moved towards Gettysburg, but they found it impossible to keep up. He was eventually left there on the side of the road and was officially listed as A.W.O.L.

Proctor had been the senior enlisted man in the unit prior to this, and the colors would now be given to the next most experienced man in the 20th Maine, which was…Andrew Tozier. Marching at night, in the rain and through the mud, Andrew led the men of the 20th Maine through the dismal Maryland countryside. He had been in the 20th Maine less than a month and was now in charge of her colors. He would take this task more seriously, perhaps, than any other task in his life.

By the time they had made it to Unions Mills, they had marched nonstop and covered 25 miles of hard slogging. They were now only four miles from Pennsylvania. In another day they would make it to Hanover and then, finally to a little place called Gettysburg and a hill known as Little Round Top.

The significance of the Union winning the Battle of Gettysburg is that it became the turning point of the war. It was decisive because there was no guarantee that the strategy and prowess of General Lee would ever fail. The South had won battle after battle with fewer men and fewer supplies. Up to this point in the Civil War, it was not at all clear if the North could eventually muster the kind of willpower, strategy and tenacity to take on Lee and his generals and gain the kind of ground needed to take back the South. The Battle of Gettysburg became the pivot around which the war turned, and a small Company from the northern state of Maine would be given a task that, if they failed, would have given the south its biggest victory yet and all but spell the end of the war within months, in favor of the Confederacy.

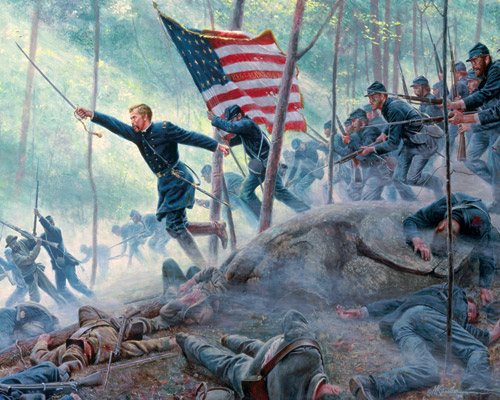

Late in the afternoon of July 2, 1863, Colonel Joshua Chamberlain and his 386 infantrymen found themselves running desperately low on ammunition. The 20th Maine had been given the task of holding the left flank of the Army’s line. The 16th Michigan held the right flank and the men from New York and Pennsylvania held the center. Earlier in the day, Chamberlain’s commander, Colonel Vincent, had told him that the thin line that the Maine men held was the left of the Uinion army’s line. “You are to hold this line at all costs!” he told Chamberlain and Chamberlain took him at his word. Earlier, 44 of his men from Company B were cut off by the enemy’s flanking maneuver, leaving only 314 men from Maine to hold the main line. Early in the day, over 800 Texans under General Hood began their assualt on Little Round Top. Later, the 15th and 47th of Alabama began to hammer into the Maine line. The Maine men held the high ground, but they were vastly outnumbered and their supply of ammunition was running dangerously low. There was little hope of holding this hill for long. Something had to happen. Something had to change.

There are times in battle when something unlikely happens, something unexpected and so unusual that it can change the course of events for everyone involved, stirring people to action they might not otherwise take. At such moments, it is all one can do not to simply stop and wonder, to gaze upon something so unlikely, so perfect. Things were looking bad for the 20th Maine. The Alabamans were moving up the hill and the Maine men had run out of ammunition. Company B was still nowhere to be seen and Colonel Joshua Chamberlain surveyed the scene at this terrible moment, only to see something that stirred his courage into even more action and caused him to make a decision that would alter the course of the battle, the war, and the fate of his country.

As he stood there, his sword drawn, he observed for a long moment the state of his color guard. All were gone, either killed or wounded, with the exception of one man – Andrew Tozier. While all possibility of snatching a victory out of the jaws of defeat seemed lost, there was one man who seemed unfazed by the carnage and confusion around him – Andrew Tozier. With the colors still flying, held in the crook of one arm and steadied against his body, he stood fast, methodically and cooly loading and then firing a borrowed musket.

Later, Colonel Chamberlain would put his memory to pen. He wrote:

“I first thought some optical illusion imposed upon me. But as forms emerged from the drifting smoke, the truth came into view…in the center, wreathed in battle smoke, stood the Color-Sergeant, Andrew Tozier. His color-staff planted in the ground by his side, the upper part clasped in his elbow,so holding the flag upright, with musket and cartridges seized from the fallen comrade at his side he was defending his sacred trust in the manner of the songs of chivalry.”

At that precise moment, is it reckoned, a total of over forty thousand bullets had been fired by combatants in the fray. With so many bullets, nearly everyone should have been hit in some way, either mortally or incidentally. Chamberlain remained unharmed. The Alabama men still lingered at the bottom of the hill. The Maine men still held it. But Chamberlain knew if the southerners rallied, the Maine men could not take another onslaught. Spurred on by Andrew Tozier’s impossible coolness in battle, Chamberlain placed himself behind Tozier and ordered a right wheel maneuver. Some say he shouted ‘Bayonets’ but it little mattered. They were out of ammunition anyway and if they were to move forward and down the hill, all they had were bayonets. Andrew Tozier led them down.

The outcome of that battle remains one of the most decisive in American Military history. The south did not take the high ground. The left flank held. Because of this, the course of the war shifted in the North’s favor. But there was something almost unworldly about Chamberlain and his fellow mainer, Andrew Tozier, at the Battle of Little Round Top. Chamberlain had been in plain sight to the enemy – he was a classical leader, a fighter, visible to all. Twice an Alabama soldier had taken aim against him and twice the soldier, inspired perhaps by Chmaberlain’s bravery and boldness, decided against pulling the trigger. In another close call, a Southern officer’s pistol misfired only feet from Chamberlain’s face. By all acounts, he should not have survived that battle.

And then there was Tozier. He stood his ground, against all odds, inspiring his own Colonel and all who saw him. That inspiration caused the sagging middle of the regiment to bolster – if they had not seen Tozier calmly firing, loading, and firing again as he held the flag slightly askew, there is little doubt that the Alabama men would have taken the hill. His courage gave Chamberlain the chance to order an unlikely attack that drove the confederates flying. It is fair to say that without Tozier, Chamberlain would not have held that hill. Andrew Tozier, son of an alcoholic, a drifter, with no place to call his home.

After the battle Tozier was offered a field promotion by Chamberlain but he asked his Colonel to withdraw it. He had more in common, it can be assumed, with the common soldiers than he did with officers. He remained in action until May of 1864 at The Battle of North Anna, where he received a wound in the left temple. Months passed before surgeons removed as many of the fragments as they could, but there would always be pieces of the minie ball in his cranium. He was not unaffected by the wound, either. Dizziness, headaches and tinnitus remained for the rest of his life. Perhaps something else happened as a result of that wound, something that changed not only his health, but his perspective, his behavior, his future.

In 1864, his term ended, and Andrew Tozier returned to Maine. He got married and became the proud father of a son. We aren’’t sure what he did before the war, but we know that in 1865, Andrew Tozier, hero of the Battle of Little Round Top, began a life of crime. Along with his half-brother, Lewis Cushman, he began to steal cattle, clothing and sundry other items. He did not act with honor or courage. He did not step forward bravely. He stole. He lied. He cheated. In 1869, the law finally caught up with him and he was implicated in a heist at the clothing store in East Livermore. He was sentenced to five years hard labor at the Maine State Prison in Thomaston. It can be rightly assumed that Andrew Tozier probably suffered from what we would today call PTSD – post-traumatic-stress-syndrome. His head injury alone may have accounted for his behavior after his enlistment was done.

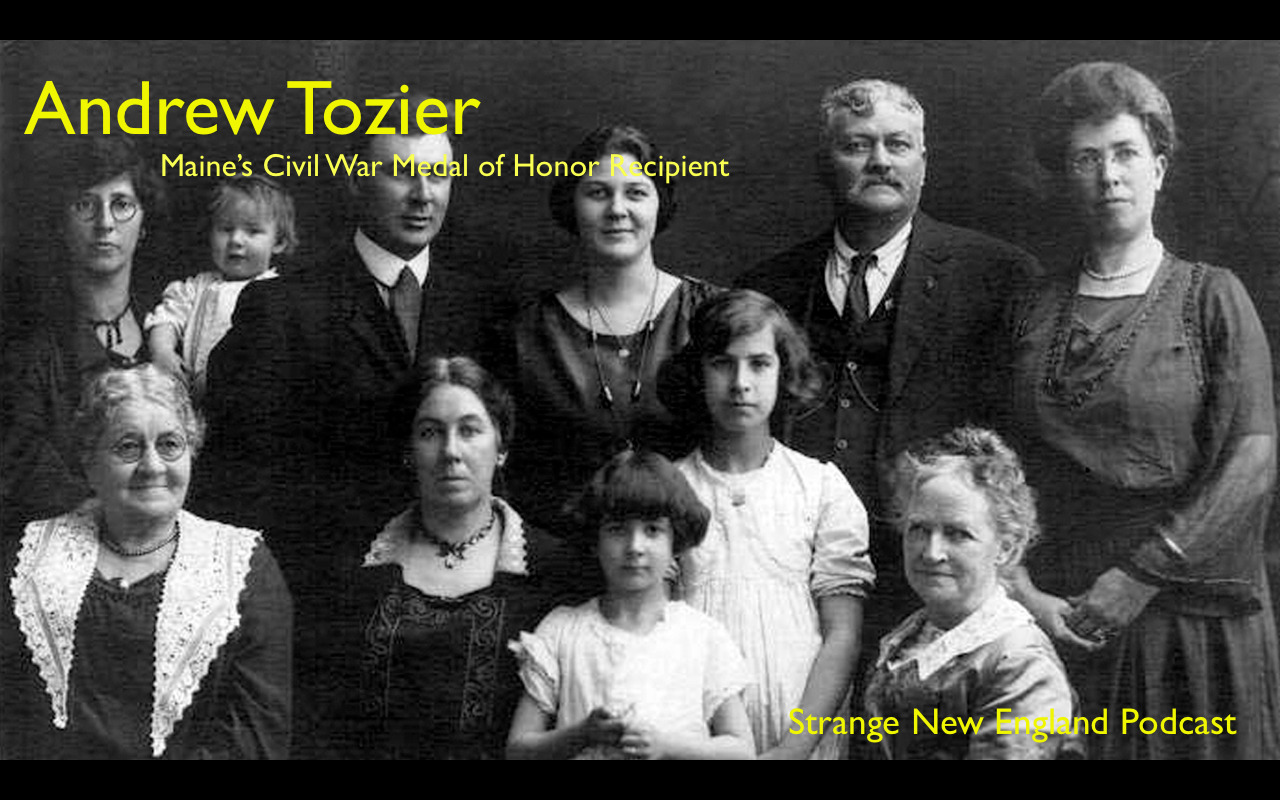

But just after he was given his cell in the prison, he received a full pardon by the Governor of the State of Maine – none other than Joshua Chamberlain, his former commander. One might think that this was a kind of honor payment, a thank you for what had happened on the sweltering day in July in Pennsylvania, but Chamberlain was better than that. He asked Tozier to move in with him and his family and he promised Tozier that he would help him change the course of his life. He taught Andrew how to read and write and gave him the kind of attention few men would have received from their former commander. A convicted felon and his wife moved in and lived with the Governor of the State and his family. In the fullness of time, Tozier’s wife gave birth to a daughter and they named her Gracie, after the Governor’s teenage daughter. By all accounts, Andrew Tozier was lucky to have such a friend as Joshua Chamberlain.

Eventually Tozier moved out and took up the straight and narrow, never again to turn to a life of crime. His health continued to falter and he found himself working odd jobs, enduring the pain of his many wounds from the war. He moved back to the area he was born and settled down to the life of a small farm – vegetables, milk, and a job in a broom factory. He had started out in Purgatory, left, took a detour into the hell that was war, and then was saved by Chamberlain, only to move back to the area of Purgatory, where it all began.

In 1890, Chamberlain wrote to the War Department, suggesting that Tozier be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions on Little Round Top in 1863. Eight years later, the award was given. It arrived in the mail at Tozier’s door.

The citation read, “At the crisis of the engagement this soldier, a color bearer, stood alone in an advanced position, the regiment having been borne back, and defended his colors with musket and ammunition picked up at his feet.” In this letter to the War Department, the Grand Old Man of Maine wrote, “He was an example of all that was excellent in a soldier” and is “one of the bravest and most deserving men.

The war took the lives of so many men. But it is safe to say that it made some men, too. Joshua Chamberlain was such a man – before the war he was a professor of languages of Bowdoin, a self-made man who taught himself Latin and Greek by shutting himself up in a garret until he understood them. He lied to get out of his teaching contract so he could join the army. He was the hero of the Battle of Little Round Top. He accepted Lee’s sword at Appomatix. He became the Governor of Maine. He became President of Bowdoin.

Andrew Tozier was made by that war, as well. Before the war, he was no one in particular, one of the many with no real place to call home. But after the war, he became a wanted man, a criminal on a spree that lasted years before he was caught and sentenced, then pardoned and cared for by his old commander who so fondly recalled that one moment in all of his life (that we know of) when Andrew Tozier decided to stand fast and hold his ground, against all odds. That one act changed the course of history – not just his own, but ours, as well. A single act of courage in an otherwise unremarkable life, except for that time after the war, when he lived the life of a common criminal.

Not many American realize that the actions of this one man turned the events of the Civil War in the North’s favor. One man and a single show of outrageous courage set into action a chain of events at led to the inevitable conclusion of the south’s surrender. One has to wonder, did he even realize what he had done for his nation?

The bravery of Tozier has been immortalized in a song by the Ghosts of Paul Revere that has been officially recognized by the state legislature as Maine’s official state ballad. It is told from the point of view of none other than Andrew Tozier,child of an alcoholic, drifter,common soldier and color-beaer, small time farmer and broom-maker, convicted criminal and Medal of Honor winner. He died on March 28, 1910. He was 72 years old.

SOURCES

Christian, James A.”Sgt. Andrew J. Tozier, Medal of Honor Recipient of the Twentieth Maine”. Gettysburg Magazine. University of Nebraska Press. Number 54. January, 2016. pp. 81-90. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/605540/pdf

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/3604/andrew-j_-tozier

“Andrew Jackson Tozier,” Litchfield Historical Society. http://www.historicalsocietyoflitchfieldmaine.org/AndrewJacksonTozier.htm

“Andrew J. Tozier.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrew_J._Tozier

Desjardin, Thomas (1995). Stand Firm Ye Boys From Maine. 2009. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195382310.

https://www.amazon.com/Stand-Firm-Boys-Maine-Gettysburg/dp/0195382315/ref=sr_1_1?keywords=9780195382310&qid=1566070875&s=gateway&sr=8-1