My name is George Miller Beard and I have a strange tale to tell you, a story so bizarre and truly unbelievable that I am certain people will doubt my report and perhaps even question my motives in discussing this subject. Still, what I have to reveal to you is the honest truth, witnessed only lately from my long journey to the northern woods of Maine in this year, 1878.

Now, before I reveal my discovery, which I am certain you will doubt, you should know that I am a graduate of Yale College, class of 1862, and I received my medical degree from the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York in 1866. During the War, I was an assistant surgeon in the West Gulf Squadron of the Union Navy aboard the gunboat New London. I have published several articles concerning the mental conditions suffered by so many after the war and was the first to name exhaustion of the central nervous system as Neurasthenia. My entire professional life has been devoted to helping those afflicted by the stresses of the modern world, a kind of deep anxiety characterized by low energy, headaches, and finally, of depression. I have fought for psychiatric reforms and have diligently tried to care for the mentally ill. I am, as I am sure you can imagine, not a man prone to flights of fancy or foolish suppositions. But that is precisely why you should listen to my discovery because, as truly remarkable and unbelievable as it is, I could never have concocted such a tale as the one which follows.

I had heard of these lumbermen of Maine from an acquaintance who had returned from a winter spent among them in the region of Maine near Moosehead Lake. This distant outpost was sparsely settled and these people were a singular one, hardly mixing with others. Most of these men he described to me were of French-Canadian descent and many only spoke a smattering of English. My friend described to me a condition he had witnessed more than once among this population that was at once both unbelievable and inconceivable. It was something that the lumbermen understood as common and not remarkable at all, though they took great pleasure in torturing those poor souls who were afflicted with it.

He explained it to me in this way. “When one of his fellows suddenly shouts an order to one of these Frenchmen, like, ‘Punch the Wall!’ or ‘throw that axe’, why, the poor fellow suddenly drops whatever he is doing and does whatever he had been commanded to do, sometimes harming himself in the process. The poor fellow is always shocked that he did such a thing, but he cannot seem to stop himself whenever he is suddenly shouted an order. It is always an instantaneous thing, and often accompanied by shouting and wild movements. Many will repeat the last word of the order they were given. That is, if he is told to slap his friend’s face, he shouts “Face!” as he gives his friend a whack.”

My friend told me that it was something that happened to many of the Frenchmen in the camps of the area and he was troubled because these poor souls were being harassed by those other lumbermen who were not afflicted in such a way. “You really should find your way up there, Beard,” he told me, “if only to see these things for yourself.”

After he had related these events to me, I found that the idea of it haunted me day and night. How could such a thing be? I had seen many ailments of the mind in my work, but never anything so odd and unique as the idea that a simple sudden suggestion could elicit such a response from such hardworking but unlearned men. I resolved to make the journey and observe this behavior myself.I would take the train to the end of the line at Moosehead Lake and journey from there to the camps with an acquaintance of my friend. I had to see for myself.

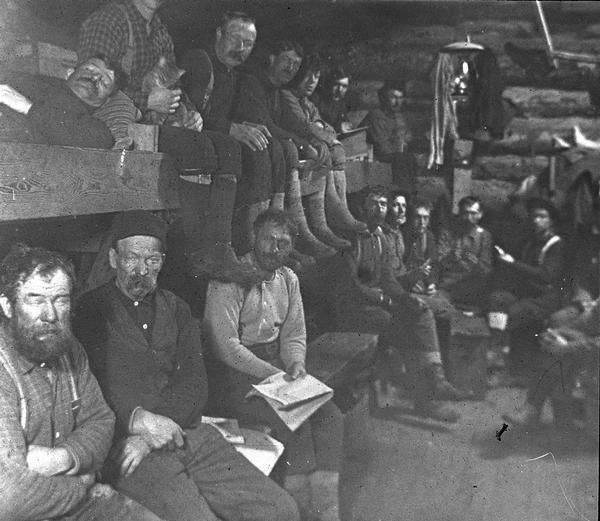

It did not take me long to discover that everything I had been told was true. I found myself in an otherwise unremarkable camp in the middle of forest. The lumbermen do most of their work in the winter cutting down and assembling piles of trees to send to the mills up or downriver in the waters of the Spring thaw. I was sitting with the men in the early evening before they all settled in to sleep. This is one of the few times in their day where they are not moving about and instead each is engaged in one of a variety of tasks before bed. One of the men, a French-Canadian man of about 40 years of age, was sharpening his axe with a stone when one of the loggers quietly stood behind him and quickly commanded, “Throw your ax into the wall!” At that moment, the poor fellow was so startled that he jumped up from his seating position and threw the ax with all of his might toward the far wall of the cabin, shouting the word “Wall!” as he did so. The room erupted with a roar of delight as all of the men found this to be extremely amusing, meanwhile the poor French-Canadian logger could be observed catching his breath and glaring at them all. It was clear this kind of thing had happened before and that he was not amused.

During my time at the camp, I witnessed this kind of behavior several times, especially after word spread that I was there to investigate the very thing. These dramatic responses by the afflicted often included the person also hitting a nearby person, screaming or, much to the delight of the English-speaking lumbermen, a stream of swearing and arm flailing that always caused a spectacle. Not believing my own eyes, I determined to put one of these men to the test. I stood behind him without him knowing it and quickly recited lines from Virgil’s Aenied, startling him. He jumped up and repeated my words, though he had never heard my words before or had any reason to be familiar with them. I found that all of the men afflicted by this strange malady were indeed from that same area and indeed, the same bloodline, more or less. They seem to be bound to automatically obey any command shouted at them, especially if it is done so as a sudden thing, to startle them. In all of my investigations and work with the mentally afflicted, I have never come across such behavior before or since. I cannot begin to explain it.”

Charles Beard never discovered the cause of the affliction which became associated with the French community of Maine, northern New Hampshire and Quebec. Later, the condition would be called “Jumping Frenchmen of Maine” and was a standard recognized condition which seemed to focus on the startle reflex that was fairly well-understood at the time. Anyone who has been jump-scared can understand the sudden rush of adrenaline and the fight or flight response that takes over the mind and body when suddenly startled. Beard published his findings and often spoke of them to august groups of physicians at the time, making it a well-known mystery. He first introduced it to the world in 1878 at the fourth annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. What he described was of great interest to those in attendance. They all understood the reaction to the sudden stimulus startling the men but NOT the obedience that followed it. Why would the poor souls suddenly do whatever they were told? Because it was not something any of these doctors would ever see in their normal, day to day practice, it remained a curiosity and perhaps even a strange kind of pseudo-legend, something that was reported to be real but still quite unbelievable. Over fifty cases were documented, fourteen of which occurred in the same family. All were French Canadian and came from very remote regions from intimately small communities. In 1885, George Tourette ventured that Jumping Frenchmen was a convulsive tic illness, but recent studies do not support his findings. Modern studies, caught on video, show that whatever it is, Jumping Frenchmen of Maine is a real malady and deserves further study.

What are we to make of this medical mystery? Certainly those afflicted live normal lives and go about their day normally. The lumber camps of Maine were very unique places with men from all walks of life cooped up for months together in social isolation, working tirelessly and enduring harsh conditions at a job that could kill them in any number of ways on any given day. These stories seemed apocryphal, could not possibly be true, but when educated men staked their reputations on the veracity of the stories, well, they had to be true, didn’t they? Other such startle reactions have been seen in the world since. In Indonesia they have a word – latah – where started individuals repeat the words that startled them and occasionally follow commands given, though never to the extent that the French-Canadian lumbermen of Maine did.

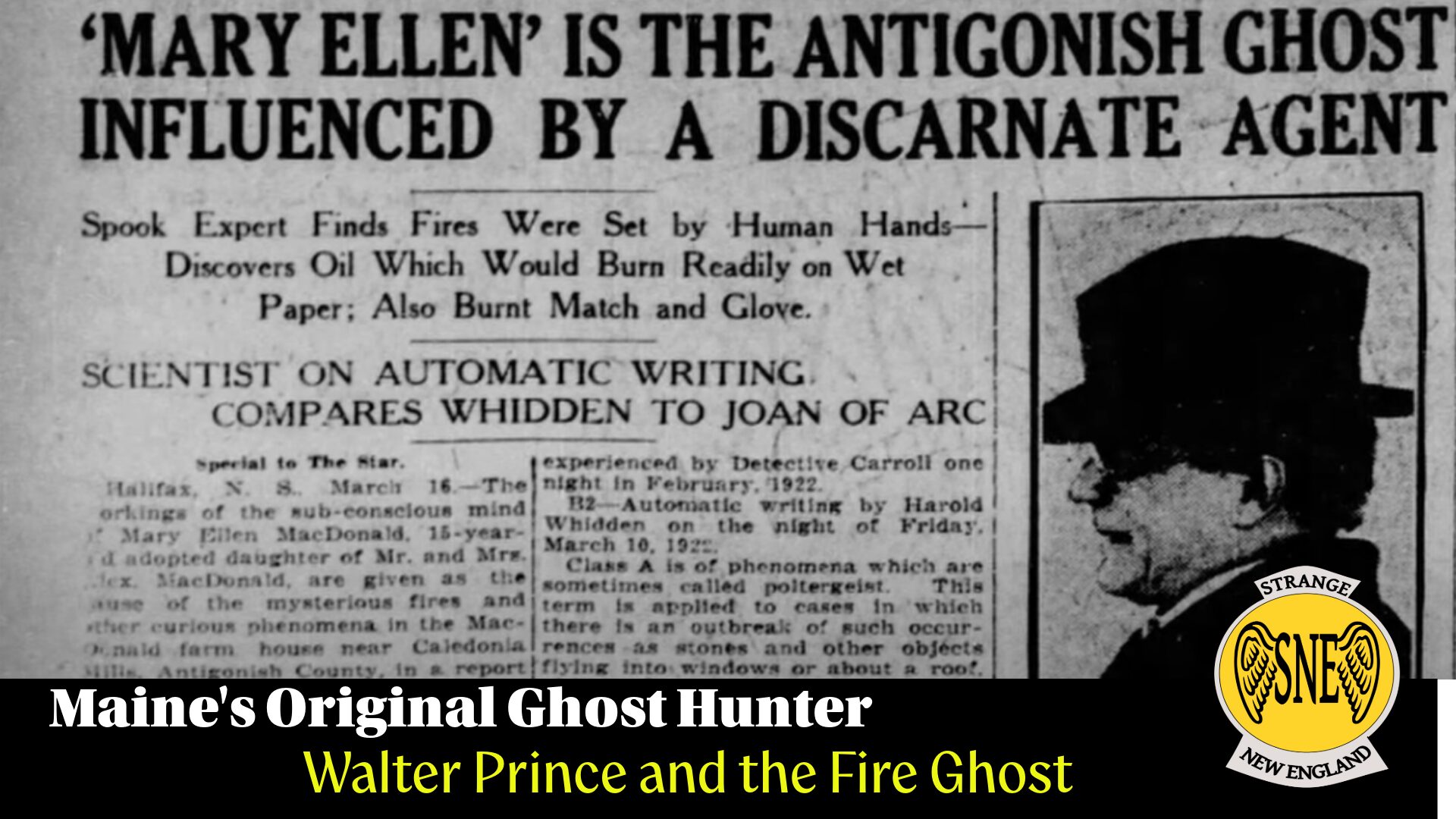

It is possible, though, that this entire study of a strange condition has everything to do with racism. In the northern woods, those lowest on the social ladder, next to the indigenous population, surely were those of French-Canadian descent, speaking a different language, coming from isolated settlements and large families and indeed, worshipping as Roman Catholics instead of Protestants: this was a people maligned and looked-down upon. The Anglo-Saxon Protestant English Speakers had a stake in the labeling of the Frenchmen as foolish and inferior. Research into the condition persisted into the 20th century, always in people of French heritage, always by people of English heritage. In a land where people of color were nearly nonexistent at the time, it is possible that those in power required someone to look down upon and without a doubt, in Maine at least, it was the French Canadian Catholics who took the brunt of their abuse. How else can we explain the fact that the Ku Klux Klan had such a large following in Maine in the years following Beard’s discovery? Only a few decades earlier Swiss missionary John Bapst, who would later become the first President of Boston College in October of 1854, was tarred and feathered and ridden out of town on a rail in Ellsworth, Maine for his Catholic faith. He wasn’t French, but he was Swiss – and he spoke French. Helen Hamlin, one of Maine’s foremost folklorists, decried the condition of the Jumping Frenchmen of Maine as “one of the greatest slanders against these people,” and dismissed it as a myth.

The condition is a strange hybrid of myth, legend, folklore and possibly, of a real condition that to this day confounds researchers. As recently as 1980, scientists in Quebec were studying the condition and still finding people afflicted with the same startle reflex, the same echoing of words, and even hitting and running when startled. Fewer and fewer cases are being reported, but the name remains. Logging camps and their long periods of isolation are a thing of the past as well, though humans will again be isolated for long periods of time once we begin long journeys in space. Perhaps in future centuries there will be a syndrome known as “Jumping Miners of Mars” or “Jumping Janitors of Jupiter.” Given the propensity for humans to label each other, anything is possible.

MUSIC CREDITS

Original Theme Music: composed. andperformed by Jim Burby

“1920 Canadian Waltz” Henri Lacroix

“Breaktime” by Keven MacLeod (Creative Commons License)

“Petite Lil Valse” by J.O. Madeleine

IMAGE CREDITS: Wikimedia Commons

RESOURCES:

Whalen, Stephen R., “The Enigma of the Jumping Frenchmen of Maine.” Maine History Journal , Volume 43, No. 1. Jan. 2007, pp. 63-78.

Simons, Ronald “Jumping Frenchmen of Maine.” National Organization for Rare Disorders, NORD.org

Howard R, Ford R. From the jumping Frenchmen of Maine to post-traumatic stress disorder: the startle response in neuropsychiatry. Psychol Med. 1992;22:695-707.

Saint-Hilaire MH, Saint-Hilaire JM, Granger L. Jumping Frenchmen of Maine. Neurology. 1986;36:1269-1271.