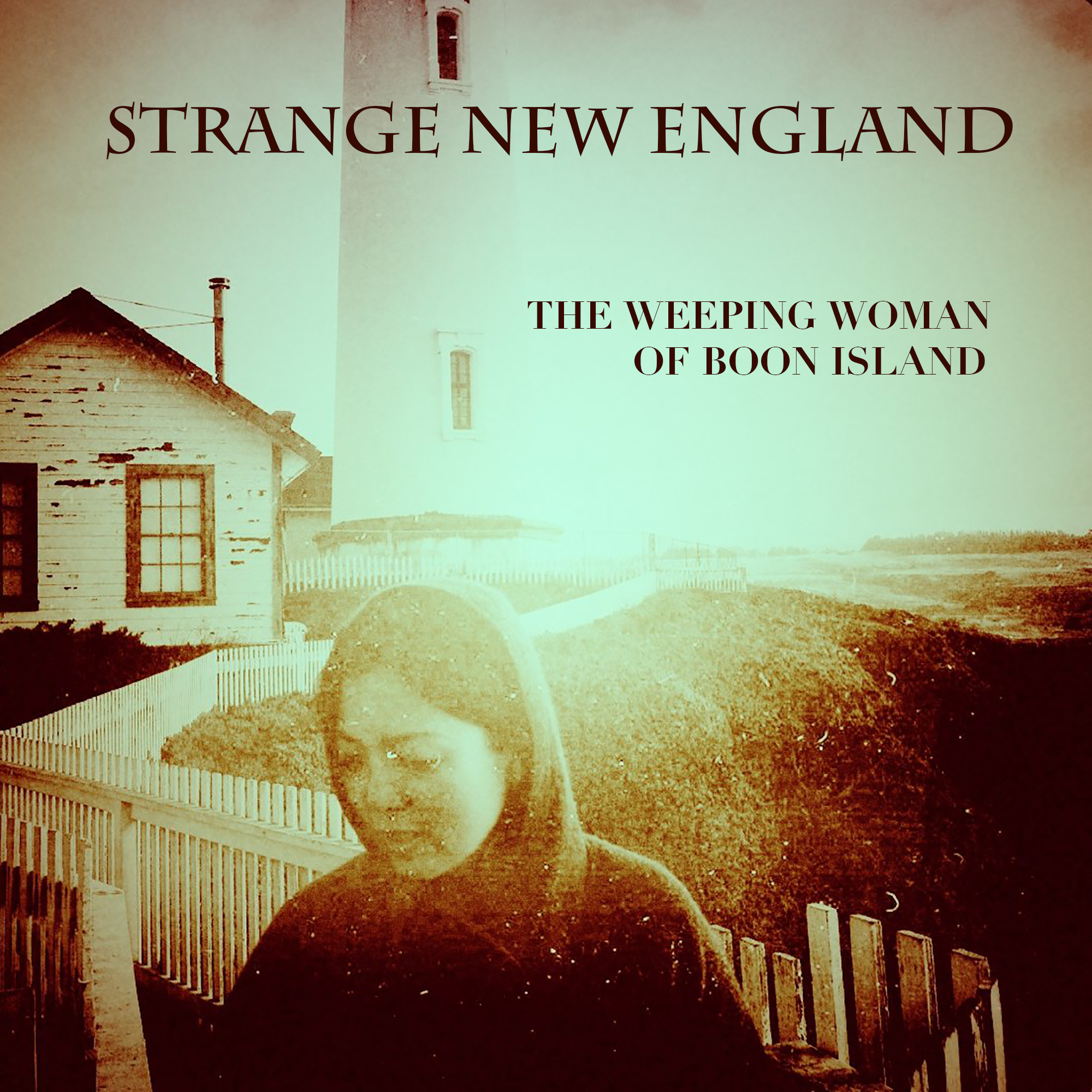

The wind is blowing. It seems like the wind is always blowing here on this rock, like a constant companion, the sea breezes wafting lightly or heavy, but always, the air is moving around you like a torrent of unseen, but not unfelt, spirits. Tonight, though, it is howling, screaming like a banshee. Outside, the elements are raging and there is no sign that this will end soon.

The light is lit, thank God. If not for your toil and attention, such a night could bring the death of many mariners who find themselves at sea so close to the rocky coast and in particular, these treacherous shoals. Winter storms tend to be the worst. As the Keeper for so many years, you’ve learned how quickly the waters can turn on you. You’ve seen the sea throw boulders from its depths against the granite walls of the light. The first three iterations of it were destroyed by the sea, but not this one. This one was built to last.

But tonight you will wait in the comfort of the keeper’s house and stand watch. There is only one place of refuge once things turn a certain corner and that is the safety of the light itself. But tonight, you will linger inside alone – thanking God that the others are safe on shore in York. There will be no sleep tonight, but as you sit there and the winds howl, you listen attentively and hope she doesn’t come again. You’ve seen her before, only when you’ve been alone on the island. She comes to the door in the midst of the rain and wind and knocks. Your heart jumps -how can someone be at the door when you are the only one on this tiny rock of an island? You remember her eyes – those pleading eyes as she looks at you when you open the door . No words are spoken and no words could ever convey the pain and worry on this young woman’s face. So as you sit there to ride out the storm, you say a little prayer for her…and for yourself. Please God, let her be restful tonight.

There is not another living soul on the island. You’ve been here for a quarter of a century already and at your age, this place has become home. It is an island, only 14 feet above sea level, a tiny place 300 by 700 feet at low tide, but it has been enough to sustain you, comfort you, even. On a good day, a clear day, you can see the coast of Maine eight miles away, see York and know that you are not completely separated. On a good day, a clear day, you have a boat that will take you there, if need be, though you rarely take the journey anymore. Your name is William C. Williams and you are the Keeper of the tallest lighthouse in New England, the Boon Island Light. Though you are alone here on this wildest of nights, you are certain of one thing, a fact you’ve come to live with, a fact you’ve come to almost find comforting – almost. Because though no living soul is with you here tonight, you know that you are most certainly not alone.

Keepers were hard to find for the Boon Island Light. The first one lasted two months before leaving his post, declaring it too isolated, too lonely, too maddening. The second keeper lasted a few years, but the duty was too difficult on the mind. The water and waves destroyed stone towers and the isolation destroyed the calm of the soul. But one man stands out in the service of the Boon Island Light.

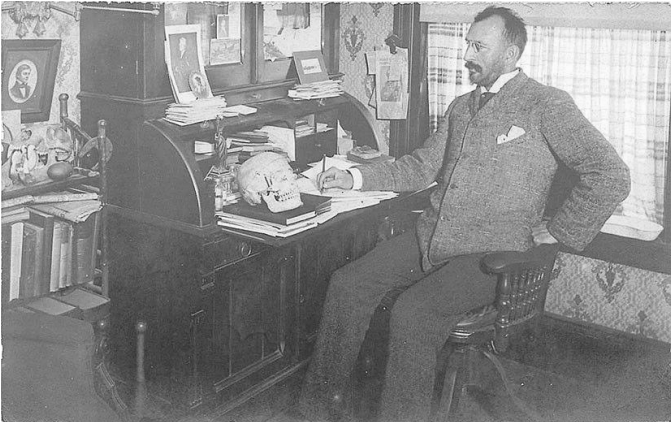

William C. Williams was not the first keeper of the Boon Island Light, nor would he be the last, but he remains one of the longest serving of all of the lighthouse keepers ever in the service. A Mainer born in Kittery, Williams first went to tiny Boon Island as an assistant in 1885. Three years later he became the principal Keeper and served in that post until 1911. Lighthouse keepers lived solitary lives, though for many of his years, he was not alone on the island. He had his share of assistants to keep him company. In the summer, he had company ,too -his family and the families of his fellow keepers who would come for the season. In good weather, some keepers would work two weeks or more, but always found themselves back on shore before long, with another person taking their place in rotation. Once, in 1888, Williams and his assistants had to take refuge in the top of the tower for three days while winds howled . But every so often, Williams found himself alone on this ragged, tiny rock. Almost.

Boon Island has a history. Over the years it has seen its share of shipwrecks and tragedy. The first recorded shipwreck was a local vessel, the Increase, in 1682. For thirty-one days the castaways, always within sight of land but unable to make the journey, subsisted on bird eggs and fishing. It was July – not a bad month to be shipwrecked off the northeastern coast. Having caught sight of a fire on a coastal mountain, they gathered anything that could burn and set it aflame, hoping someone would see the smoke. Ten days later, they were rescued. They were lucky, unlike the men who found themselves shipwrecked there on December 11, 1710. The English ship, the Nottingham Galley, under the command of their hated captain, John Deanne, found themselves so desperate that they ate their ship’s carpenter. Rescued a little more than a month after the storm tossed them ashore, the remaining crew left their prison with the rumor of cannibalism that would haunt them all until their own deaths. Many lost fingers, toes and in one case, half a foot, to frostbite. But at least they still had their lives. Perhaps when terrible things happen in a place, something remains, something remembers.

William C. Williams, the long-time keeper, might have thought he heard their cries and at least imagined their terror and desperation, especially when he found himself alone. Always keenly aware of how close death was no matter where he stood on the island, he recalled as a 90 year old retired man in Kittery that one of the greatest pleasures of his life was to simply walk in his front yard without having to worry about being swept to his death if he strayed too close to the ledge and shore of Boon Island.

In 1805, while rebuilding the first tower that had been destroyed by the violence of the elements raging, three men drowned there. This little shoal had seen the dark shadow of human death more often than it should have. How strange that so many perished here, within a mere six miles of the continent.

There were other stories of loss and pain, but one of them might have touched him more than the others. Unlike the others, it was a love story, a ghost story. There are no names given, no facts that can be researched because it is, after all, a spirit tale with no proof. William C. Williams was not a man of many words and his speech, they say, was simple, direct and to the point. He was a reader and a thinker, a man of good humor who did not easily become excited or upset. He was a man in control of his own mind. Perhaps that is the secret to his success as one of the longest serving lighthouse keepers in the service: nothing phased him so much that he could not complete his daily appointed rounds. But that doesn’t mean he didn’t experience visits from her – the woman who weeps as she walks the stoney ledges of Boon Island.

It is one of those nineteenth century stories you might find in a magazine of the early Victorian era, a melodramatic tale, complete with an etching of a stone tower against a black backdrop. Picture a lonely, isolated lighthouse just off the Maine coast, kept by a newly appointed lighthouse keeper and his young wife. Together they ensure that the light remains lit. It is a romantic setting for a newly married couple, a place isolated but beautiful in its own wild, hard way. All they have to sustain themselves on this island is each other. Together, they keep the fire burning.

But one night the winds begin to blow and the barometer falls and the waves begin to pound and throw stones from out of the deep onto the island and against the tower and their house. Fearing that their small boat, their only way off the island, might be lost to such a tempest, the keeper ventures out to the launching station to make sure it is secured and in a wild wind is tossed back against the rocks, hitting his head and rendering him unconscious. His wife calls for him, but he does not return. In a panic, she ventures out into the growing storm and finds her husband there in the rocks and the salt pools. She rushes out to him. To her relief, he is breathing but she cannot call him back to consciousness. With Herculean strength, she hauls his body back to the base of the light. Pulling him inside, she shuts the great door against the tempest. Tending to him, she knows that the light has to keep going. Walking the 168 steps to the top, she makes sure the light keeps burning for the next five days – five interminable days as she runs back down to the base of the light to tend to her husband, then back up the winding staircase to set the light.

After five days, the kerosene runs out and the local sailors notice the absence of the light. The storm finally abated, the rescuers make their way to Boon Island. Imagine them calling for someone as they breach the shore. Imagine them going into the flooded house and calling, but hearing no answer. Finally, they open the door at the base of the lighthouse and see her there, cradling her husband’s ashen gray head in her lap, running her fingers through his hair, her eyes red and wild, her mind savaged by the experience. When they try to tell her that her husband was dead, she can not bear it. Her mind unwinds and she becomes hysterical. The rescuers carry her, raving, off the island, all the while with her shouting that he isn’t dead, please, he isn’t dead, he can’t be dead!

Legend relates that she died a few weeks later. That was tragedy enough, but the legend wasn’t born until tales of a woman knocking at the keeper’s house door began to circulate among the good people of York Village.When the door is answered , a young woman looks frantically at the person answering and then turns and runs to the lighthouse, only to disappear. Young keepers told stories of hearing a woman’s voice echoing in the tower while they tended the light, always alone. Her presence lingers. William C. Williams, long time keeper of the Boon Island Light, must have had a brush or two with the keeper’s wife. Of all people, surely he could understand her fear, her isolation and her courage. If anyone could understand her, it would be him.

So a tapping at the window in the night might be a stone thrown from the sea, or perhaps a gull, but just as likely it could be a woman’s hand seen just at the edge of the windowpane. And as he looked out from the light down to the tiny island from the lighthouse chamber, could it be a trick of the light or was that a woman walking the shore, a woman who, by all rights, should not be there. A thought haunts him – why has he never followed her as she beckoned? And if she knocks tonight , will he follow her to the lighthouse? And if he does, will that set her free. Will he have a glimpse into her recurring nightmare? Will he see what she sees? He worries about her, quietly of course. He keeps his counsel and doesn’t talk about it to the other keeper or his wife on shore. She is plainly suffering, but what can he do?

No one lives on Boon Island anymore. The lighthouse is automated like all of the others along the coast. Oh, there are visitors from the Coast Guard from time to time, but the days of keepers and their assistants are long gone. No one tends the light to make sure it doesn’t go dark and if there are knocks on the Keeper’s house door, they always go unanswered.

Music Credits: Myuu – “Bad Encounter” Myuu – “Disintegrating”

Theme Music: copyright 2015 James Burby

Audio Editing and Mastering: James Burby

REFERENCES:

“Boon Island Lighthouse History” newenglandlighthouses.net

“Boon Island Light” wikipedia.org

“The Haunting of Boon Island” seacoastonline.com