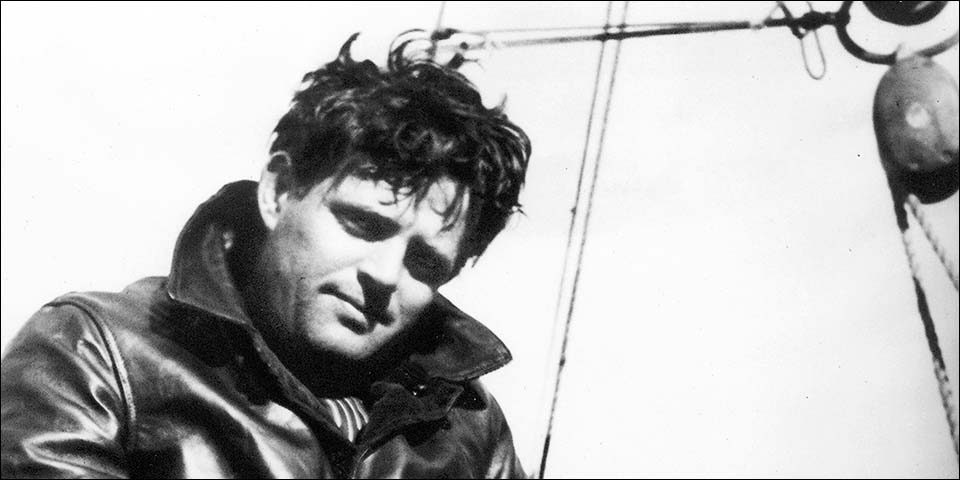

Anyone who has completed high school in the English speaking world knows of the work of the great American author, Jack London. The man who brought the world such timeless adventure classics as The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and the dark short story, “To Build a Fire,” was also a social activist, boxer, sailor, dock worker, and one of the first fiction writers ever to obtain worldwide celebrity and amass a fortune with his writing. He was a character much larger than life who in his time took on a large number of jobs to make a living before discovering his talent as a writer. He worked in canneries on the docks of San Francisco as a child, then became a seal hunter and sailor, and took the time to tramp about the West before attempting and ultimately not completing college. From the call of the Yukon Gold Rush which figures so prominently in his writing to working as a war correspondent in the Russo-Japanese War, London was like a rolling stone, never content to settle down and never able to find that niche in the world where he could comfortably fit. In so many ways, he was the quintessential American man of his time.

The apple didn’t fall far from the tree. If Jack London could be accused of being a character, a rolling stone, or an opportunist, one need look no further than the man that most London scholars believe to be his father, William Henry Chaney (1821-1903). Though London was never influenced by his father’s actual presence, perhaps his DNA had something to do with his inability to settle down. William Henry Chaney was born in a log cabin in Chesterville, Maine on January 13, 1821, one year after Maine officially became a state. His father died when William was nine years old and the family farm could no longer support the family without his father. In the 1820s and indeed, up through the Great Depression, it was not unusual in such rural areas for children to be ‘sold’ to other farmers until their 18th birthday or until they managed to run away. Chaney’s mother ‘sold’ William, as well as his younger sisters, binding each of them to a childhood of labor.

William was an intelligent and somewhat ambitious young man who was determined to escape the terrible treatment he felt was administered to him in his degraded state. He was passed around from farmer to farmer in the Chesterville area where he was treated, in his words, as a ‘work beast.’ At sixteen years of age, William ran away from his indentured servitude in Chesterville, never to return. He was alone, he was on the make, and he had nothing to lose. There was work available and he tried the route of manual labor for awhile. From a sawmill job to the carpenter’s bench, William Henry Chaney gave an honest day’s work a chance, but it did not fulfill him. He hated manual labor mainly because he had discovered his love of reading and study and possibly the idea that we somehow too smart for this kind of work. Twelve hour days left precious little time to progress in his studies. One can imagine him taking his break alone in a quiet corner of the sawmill so that he might read three or four pages of tiny text from one of the dog-eared books he managed to scavenge from the few rare places books were available in rural Maine at the time, his co-workers throwing him dark glances and making fun of the young man who took on airs. Even the deacon of a local church in the area informed him that he was “the Devil’s unaccountable.” Later, he would spend much of his energy deriding organized religion and Christianity, in particular.

Perhaps such cruel treatment, such derision and exclusion from the society he found himself in turned his dark eye to a cynical view of the world. He wanted to break free, to escape from the daily drudgery that was the mundane existence of those he saw populating his world. He found his way to the coast of Maine, signed on to a fishing schooner and did what so many New Englanders did in those days – he went to sea. He worked for two years under the mast when he decided to join the American Navy, perhaps to make a career and finally settle. It did not agree with him and nine months later when he found himself in Boston in July of 1840, where he promptly jumped ship, never to return.

Life as a deserter from the Navy meant traveling at night, under cover, and incognito. He was still hungry for adventure, for the life of a character from one of the books he so eagerly consumed. He followed the tracks of so many and found his way southwestward to the Gulf Coast. He signed onto a flat boat on the Ohio River, headed to New Orleans. But Fate would not allow this adventure to continue. When he fell sick, he was left by his captain on the riverbank one night, with no money, no prospects and no real experience that could help him find employment. He knew how to work on a farm and this area was full of them. Soon, he had work and clothing, food and most precious of all, the sympathy and kindness that he had never known in Maine.

William Henry Chaney decided to make his living with his mind and not with his hands. Whether or not he actually studied the law is in question. However, he managed to gain some employment in the courts. Somehow, in some way, he would use his mind to create the life he longed for so dearly. As he recounted in his book Primer of Astrology and Urania, he did not change his wandering ways for long, going from one job to another, punctuated by periods of reading and studying, preparing his own world view which he would later share with the world. “School teachers disliked me because I repudiated so much of science and philosophy that they believed true. Lawyers disliked me because I would not run in the old rut of ‘precedents,’ unjust laws, etc., but more especially because if employed to prosecute one of them I did not spare him any more than I would a common thief…” Chaney was not a warm, welcoming, live-and-let-live kind of person and from his own words, it is easy to assume that he alienated nearly every person with an education who he came across. This anger and raging against popular thought and practices seemed to do him no good – he roamed from city to town without employment for long. Though he claimed that for ten years he had practiced law and was an editor, there is no hard proof that he actually did any work in those two areas. He writes, “I lost everything I possessed, all of my books went for my rent, I could not find employment of any kind.”

He disappears from the written record for over nine years, only to turn up again in the field that would eventually become his chosen life profession: astrology. In 1866, Dr. Luke Broughton, a famed English astrologer who was the first person to use the horoscopes of famous Americans in his work, took on a new student. Before Broughton’s arrival in the United States, astrology was virtually unknown among the populace. He had come to America to spread the word about it, but it would be Chaney who would do the legwork and public speaking and it was Chaney who would inform the American people about the virtues of the study of astrology. Astrology would become the one ‘science’ that Chaney would choose as his life’s work. He seemed to have a gift with words and for public speaking and invention, as well. What he did not know about astrology, he created. His idea was that if you knew a child’s horoscope, you could then help that child grow into a thriving and prosperous adult. What Chaney did for the study of astrology was introduce rigor into the practice. His students were taught to use an organized approach to the practice of studying the stars, rather than simply the random readings given in those days. He became very liberal in his views, supporting free love, equal rights, and coming out against organized religion.

Once the transcontinental railroad was completed, Chaney was on the train to the West. Married at the time, he told his wife he would be gone for only a short while. He did not return for seventeen years. He found himself in Oregon in the early 1870s and he claimed in his book that “I enjoyed the friendship, ‘in private,’ of U.S. Senators, Congressmen, Governors, Judges of the Supreme and lower courts, etc., but they were timid about recognizing me in public, except to salute me pleasantly. I helped many a one to his position, working in secret, but they dare not reward me openly, although in private they were my best and truest friends.” These claims, of course, cannot be disputed or dis-proven but they do illustrate the state of Chaney’s mind at this point in his life. To say that he had delusions of grandeur or or at least grandstanding might be exaggerating, but as essentially a penniless, unknown man, it is highly unlikely that he set up the entire structure of the government of Oregon on his own, behind the scenes. The one thing that we do know for certain is that it was while he was in Salem, Oregon that he met and took up with Flora Wellman, Jack London’s mother. They moved to San Francisco to start their life together.

Flora’s life is not as much of a mystery as Chaney’s, though it too strays into strange areas. As a child, she lost her mother when she was four and then she suffered from Typhoid Fever which left her under five feet tall with thinning hair and very poor eyesight. From a once-prominent family in Ohio, Flora fell on hard times when her father lost his fortune in the great financial panic of 1858. She was fifteen years old at the time. After working for Sanitary Commission during the Civil War, she disappeared from history for a time. Eventually, she found her way to Oregon and to the side of William Chaney. Perhaps she did not know that he was already married back east and that he had married again, making him a polygamist. Perhaps it did not matter to her. Flora was not so much an adherent of astrology as she was a spiritualist who led seances and gave lectures. Seances were a part of her daily routine and since spiritualism and astrology were both in vogue in the West at the time, Chaney and Wellman made a good living. Things were looking up for the polygamist astrologer and his short medium wife.

When Flora found herself pregnant with the boy who would become Jack London, she also found herself at odds with William Henry Chaney of Chesterville, Maine. He insisted that the child was not his and that all of his previous relationships with women were childless, therefore proving that he was sterile and therefore incapable of siring a child. She must have strayed with another man and Chaney demanded further that if she did not destroy the child, he would leave her. “Flora, I want you to pack up and leave this house,” he said. She replied, “I have no money and nowhere to go.” She left the apartment in anguish. When she returned, Chaney had sold all of the furniture.

She is mentioned in the San Francisco Chronicle of July 4, 1875 with the headline, “A Discarded Wife.” The article describes how Flora first attempted suicide by taking laudanum. When this did not work, she shot herself in the head but the ball glanced off, producing only a flesh wound. Chaney did not seem to care and showed no interest, never claiming the child as his own. Luckily, Flora had friends who kindly took her in and on January 12, 1876, she gave birth to a son named John, later Jack. A year later, she married a a disabled Civil War veteran working as a carpenter named John London, a widower with two young girls of his own. Flora never told young Jack that his real father was William Chaney until he as much, much older.

William Henry Chaney spent most of his adult life predicting the lives of newborn children in the form of their astrological charts. Apparently he never read his own chart, or perhaps he should have created a chart for the boy who would eventually become world famous as one of the greatest writers of the 19th century. After he parted company with Flora, he continued his wandering work with the teaching of astrology and the production of astrological charts for customers, all the while deriding Christianity. He certainly lived long enough to be aware of the great Jack London and his exploits. He died at the age 82 and was buried in a snowstorm in Elmwood Cemetery in Chicago. Years later, he was disinterred and buried elsewhere in an unmarked grave.

Was he a charlatan? Almost definitely. Was he any different from thousands of other men of his time riding the wave of the American nineteenth-century idealism that defined the age? No, not so much. He was ambitious and eager to move forward, always toward tomorrow’s horizon and away from the sensibilities and responsibilities of today, including that possibility that he had indeed fathered a son who would grow up to make a huge mark upon American literature.

SOURCES

1 COMMENT