Are you bald? Do you know any bald men? Of course, there is usually a perfectly rational, medical reason for the loss of hair in the male of the species – male pattern baldness, alopecia, or too much testosterone, among others. Before we discovered the scientific reasons for hair loss, we used stories to help us understand it and this tale from the logging camps of northern New England and the Maritimes is one of the most famous. Remember, be kind to our fine feathered friends – any bird could be somebody’s mother…

Many of the animals of New England have their own story, with each one reflecting either the animal’s personality or their place in history. Both prehistoric and historic New Englanders have always seen a part of their own personality when they watched animals in their natural environment and it is that perceived relationship that brings us a very strange tale from the northern woods from the time of the big logging camps.

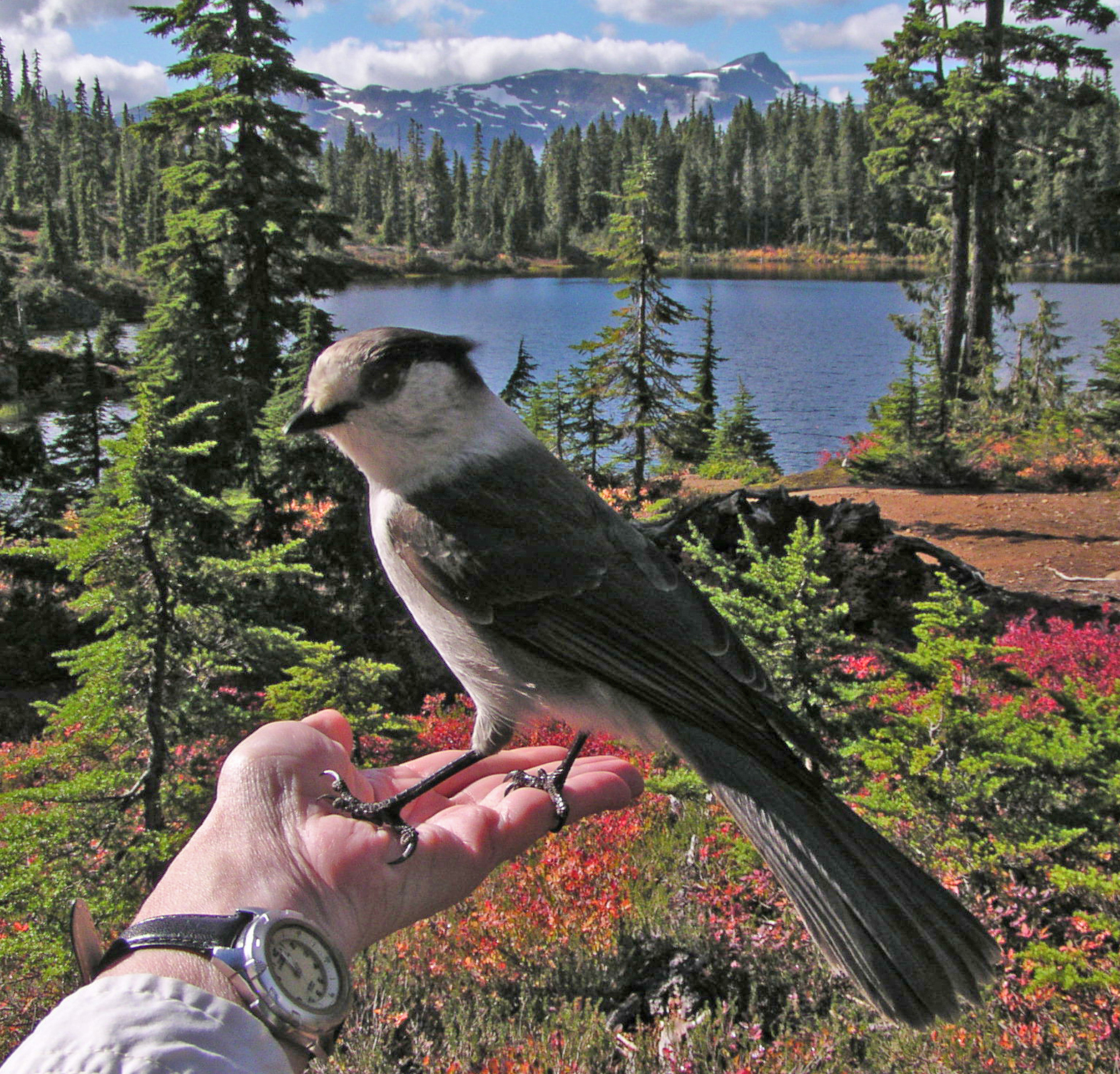

One specific species of bird, common to the deep woods of Maine and Canada, has become a more obscure story as the logging camps in New Brunswick and Maine were closed. Back when logging was a larger industry in the north, however, the stories associated with the Canada Jay or “Gorbey” were commonplace among the men who worked their trade in the deep forests. Because the Gorbey is a deep woods bird that doesn’t venture into urban settings, it’s stories became obscured as the lumberjacks moved out from the logging camps and into alternative jobs.

It was the work of folklorist Sandy D. Ives, founder of the Northeast Archives of Folklore and Oral History, that helped record the stories of the Gorbey and save them from being forever lost. Through the audio and text recordings that Dr. Ives made, information about this bird’s behavior and it’s impression on New Englanders can be seen through the tall tales it inspired.

The first aspect of the legends are the folk names the Gorbey has been given: Gray Jay, Camp Robber, Venison Hawk, Hudson Bay, Caribou Bird, Moose Bird, Meat Bird, Grease Bird, Woodsman’s Friend, Whiskey Jack or Whiskey John. The original Native American name for this bird is the ‘wisk-i-djak’, which is similar to ‘whiskey jack’. Both names are derived from the bird’s call. Other unusual traits that the Gorbey possesses are further implied by their names. The name may come from either Scotland or France. It might be either from the French-Canadian pronunciation of the French word “Corveaux”, for a bird who is related to ravens and crows. The Scottish origin might come from the word “Gorb”, which has a double meaning: ‘glutton’ and ‘unfledged bird’.

According to some sources, this bird helped hunters to find moose or caribou. This bird would signal to a hunter where they could be found and in exchange, the hunter would give meat to this bird to eat. Those who tell this story suggest that this is because the Gorbey is not satisfied with eating ticks and fleas off moose and caribou and wants a more substantial meal. The Native Americans believed this animal had a powerful spirit living inside of it and would listen for its call while hunting, as well as give the bird meat after the kill was made. Another Native American legend associated with the Gorbey states that cold weather comes when someone pulls a few feathers off of the bird’s chest. Whether this was a magical spell or a warning against harming the birds is not made clear.

In later years, when logging camps were more commonplace in rivers across Maine and New Brunswick, the Gorbey did not have to get hunters to give them filling meals anymore. It was said that whole flocks of them would fly out of the trees and steal food straight from the lumberjack’s hands and lunch pails. While only one or two would show up on the first day, more and more would appear to make off with the lunches of the lumberjacks as time wore on. They would also hide in the clothes of the lumberjacks, not caring if they were worn or not. The origin of the names “Woodsman’s friend’ and “camp robber” is probably inspired by these antics.

For lumberjacks, these birds were a great source of amusement. Most were happy to see these birds despite losing their food to them and were entertained by their tricks in the air and on the ground. In remote and quiet forests, such entertainment was certainly a welcome sight.

Others were not happy to feed such a feathered thief.

Whatever a lumberjack’s feelings were about the gorbey, there was a strict taboo against harming these birds. The work of the lumberjack was fraught with danger and as a result, superstition ran rife. The bird was regarded as a lucky animal like the albatross from The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Sometimes, it was because the bird was a lumberjack who came back from the dead to rejoin his companions. Others believed that if they hurt a gorbey, the injury would be returned on them.

This retelling of “The Man who Plucked The Gorbey” has elements drawn from the book Will O’ The Wisp: Folk Tales and Legends of New Brunswick by Carole Spray” and the records left by Dr. Sandy D. Ives.

There was once a gorbey who frequented a logging camp named Old Ferguson. He was named after a lumberjack who had died at work. The lumberjacks believed this bird was a reincarnation of their dead comrade because he had a big appetite and because he wore a grey coat and black hat that reminded them of the bird’s feathers. They enjoyed Old Ferguson’s antics as a part of their midday meal and welcomed him and the flocks of gorbeys as if they were equals.But a new lumberjack came to work at the camp who was not pleased with entertaining this bird. He is given many names, but let us call the man Archie Stackhouse. He grew angry with this bird’s habit of snatching biscuits from his hand as he was about to eat them. Archie swore he would kill Old Ferguson once he got his hands on him. When his comrades warned him not to harm the bird for fear of bad luck, he scorned this as a foolish belief. It is also relevant to mention that Archie Stackhouse had handsome black hair he was particularly proud of.

According to Carole Spray’s version, Old Ferguson’s favorite snack was biscuits soaked in whiskey. One cold winter day, the bird was fed this treat and soon grew so drunk, he could not fly straight. One kindly lumberjack took this bird into a mitten and let him sleep off his binge. But Archie took his chance to make good on his threats. He seized the small, drunk bird and ripped off the feathers from his back and belly, leaving him very naked with only wing feathers spared. The bird tried to fly up with the feathers he had left but fell down and died instantly. (Dr. Ives’ records states that the poor plucked bird merely died of exposure overnight in February.)

The lumberjacks were appalled at this turn of events, but Archie went to bed satisfied with himself. In the morning, there was a surprise waiting for Archie. He saw in the mirror next to the washbasin that all of his coveted black hair had fallen off of his head, leaving his chin and head bare. He never grew this head of hair back again.

According to Carole Spray’s telling, if there was a lumberjack who was bald or lacked hair, he would usually be asked “Are you the man who plucked the gorbey?” as a joke. An alternative version from an article written by Dr. Ives’ included another character: a bad tempered Frenchman who gave Archie a sound thrashing after he awoke to find his head bare.

In the audio retelling recorded by Dr. Ives, Archie is given a specific job at the logging camp. He is described as a ‘wangan man’, who was the manager of the outpost store. He was responsible for minding and managing supplies for the whole camp as well as selling goods to the lumberjacks. Even in those camps, the exchange of money was still a necessity.

Dr. Edward Ives Interview with Charles Sibley – 11-30-58 “The Man Who Plucked the Gorbey”

The stories of the gorbey do not end there. According to an informant whose account is on record at The University of Maine, there is an old and simple yarn about a logging camp cook who one day found a gorbey carrying off three stale doughnuts that had been thrown away. Considering that the gorbey is the size of a robin, this is an impressive feat for a bird of that size. Another story is a folk song called “Tom Cray”, from Northern Maine. The song warns unwary lumberjacks of gorbeys and blue jays big enough to carry off men to eat. Another version, written on the blog New England Folklore names the bird ‘Esau’ after a foreman who died. For those who know Hebrew, a hint of what’s to come is already given. “Esau” means ‘hairy’ in Hebrew. Whether this was an intentional hint or not is not mentioned. There are even variations that involve lumberjacks who suffer broken bones after they broke bones on gorbies. In these versions, lumberjacks break either a leg or a wing on this bird and as a result, suffer a broken leg or arm.

All of these stories say a lot about the attitudes of those who told them. It reveals a continued respect of nature that may have it’s origin with the Wabanaki tribes, but continued on through to the lumberjacks whose respect to the bird was born out of a continued necessity to respect nature and the unexplained. Both the Wabanaki and the lumberjacks understood the perils nature presented and knew that humility and kindness was important to warding off danger and death.

It is also possible that Native American and European New Englanders have always found entertainment from these intelligent and bold birds and a unique bond between animal and man has been formed that, to this day, continues in the deep woods. Even today, campers in the Northern woods are greeted by gorbies, who follow humans for their food not because any human encouraged it, but because their instinct to find food draw them to us naturally.

This article is published in memory of Sandy Ives, the foremost folklorist on the legends of the gorbey and one of the finest ethnographers at The University of Maine. His organization, The Maine Folklife Center, is still active, working to preserve Maine’s rich folk traditions through preserving languages, stories photographs, recipes, songs and recordings.

You can use this link to access the Facebook page, where they talk about their work as well as advertise their events. You can also find them on the campus at The University of Maine and at the Annual Maine Folk Festival in Bangor.

Resources

Places-Moosehead Lake “The Man Who Plucked The Gorbey”

New England Folklore At Blogspot.Com: The Gorbey-Pluck at Your Own Risk

The University of Maine-The Man Who Plucked The Gorbey Audio Recording

photo credit – Strathcona Wilderness Institute