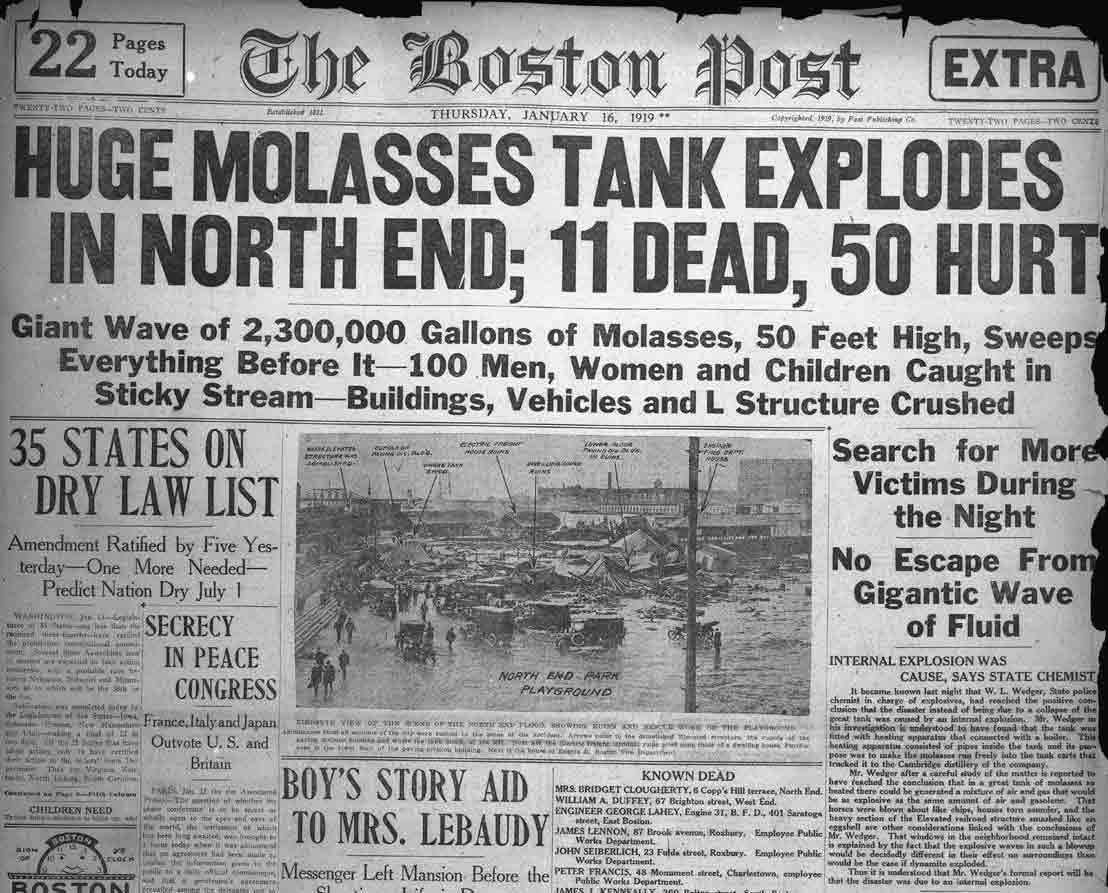

Strange things happen. Fish sometimes fall from the sky. Unexplained lights perform strange maneuvers in the night sky. Children claim to ‘remember’ past lives. While all of these must be taken with more than a modicum of suspicion, there are strange occurrences in history which are without a doubt real and actual events. The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919 is one such event. Be careful. Though you might be tempted to laugh at the idea of a flood of molasses as ludicrous and unbelievable, the series of tragic events that took place on January 15, 1919 left twenty-one people dead and a score of people injured. As strange and as sickeningly sweet as it sounds, Boston experienced the world’s only known disaster caused by a sugar by-product.

Molasses was a staple food in colonial New England. Slave ships emptied their cargo in the West Indies and filled their holds with barrels of molasses and then headed to the colonies. Sugar was one of the most expensive staples in the colonial pantry, so molasses was a welcome and much less expensive alternative. Colonists used it in the production of beer and rum and you cannot have true New England Baked Beans, brown bread or pumpkin pie without it.

Most people are unaware that molasses had a very important role to play during wartime and it had nothing to do with food. As any home brewer will tell you, sugar and yeast together create something very powerful: alcohol. Ships from Cuba, Puerto Rico and other islands in the West Indies would dock and pump out thousands of gallons to later be carried by rail car to the Purity plant in Cambridge where it underwent the process of conversion to industrial alcohol. Then, the alcohol could be used in the mass manufacture of munitions and explosives, adding to the war effort and making a lot of money for the United States Industrial Alcohol Company. Since the outbreak of war in 1914, overseas demand for alcohol had strained domestic resources and the British, the Canadian and the French governments could not get enough. With a paltry twenty percent of the molasses shipped to American converted into rum, a whopping 80 percent of the substance was turned into a major ingredient of weaponry, especially of dynamite, smokeless powder and other explosives.

In order to facilitate the collection and distribution of the molasses, the company built a massive holding tank, fifty feet high and ninety feet in diameter capable of holding as much as 2,300,000 gallons of molasses. The tank stood in the North End, near Boston Harbor and the historic section of town that housed the Old North Church and Paul Revere’s House. The tank was very to close the Copp’s Hill Burying Ground and Commercial Street. It was one of the largest structures in the area and it towered over many houses and commercial buildings in the area, always in the background.

It was built the same way that metal ships like the Titanic were built at the time with sheet steel and rivets overlapping at the edges. Like the Titanic, the Boston tank had a major flaw in the steel common to all steel manufactured in the early part of the century: it was made with very little manganese, an element that strengthens steel making it capable of withstanding great pressure without cracking.

From the very beginning, people became used to seeing the dark brown stain of molasses running down from rivet holes all over the structure. Children would be dispatched with containers to visit the plant and collect as much of the run-off as they could. Though most of the people who actually lived in the area were Italian immigrants and therefore out of the mainstream of Boston life, it became a problem for the company that owned the tank. They did not want word to spread that there was a problem with it. Something had to be done.

In their wisdom, the people at the US Industrial Alcohol Company found a way to fix the issue: they ordered the structure to be painted a molasses brown, so the leaks could easily be masked. Although the structure was only ever filled to capacity three times before the accident, it was on constant use and was never shut down and emptied for a complete inspection. Perhaps no one could imagine that a substance so obviously harmless as brown liquid sugar could ever be deadly in another sense, a very real and overwhelming sense, without ever being converted into alcohol.

January 15, 1919 should have been a quiet day at the molasses tank. The ship Miliero had unloaded her cargo two days ago. It had taken everything that the pumps had to urge the semi-solid sticky substance through the tubes in freezing weather, but after this unloading, there wouldn’t be another ship for at least three months. During those three months, the molasses would be slowly shipped to the Purity plant to be converted into alcohol bound for munition factories. A few who survived the event can remember hearing the shifting and gurgling that occurs when molasses is actively fermenting and perhaps that process helped speed along the final conditions that led to the failure of the hoops at the bottom of the tank and the rivets along the seams.

At 12:41 PM, the tank gave way. The headline of the Boston Daily Globe for the next morning read “Molasses Tank Explosion Inures 50 and kills 11. Death and devastation in wake of North End Disaster.” By the time they found all of the bodies glued to the ground in the muck and immovable mire, the number of dead had risen to twenty-one. What happened directly after 12:41 was witnessed by hundreds. A black wave of death flowed much more quickly than might be imagined, twenty-five feet high and one hundred and sixty feet wide.The wave was so heavy that it essentially smashed the waterfront like a bomb. One half-mile of Commercial Street was destroyed and it flowed in all directions. Rivets snapped off and turned into projectiles: steel bullets randomly filling the air as the tank continued to break. The Engine 31 Firehouse was ripped from its foundation and almost made it to the dark waters of the harbor. “Men and women, their feet trapped by the sticky mass, slipped and fell and were suffocated,” reported the Boston Globe in a remembrance of the event in 1968. Brick tenements, storefronts, various wooden structures were all torn and shattered. Anything that stood in the path of the oncoming molasses was hit by the heavy liquid hammer of the cascading molasses. What wasn’t destroyed or swept into Boston Harbor was glued to the ground or covered by the rubble. Cellars were filled with molasses. Electrical poles and live electrical lines snapped and popped in the thick detritus of the event.

The rescuers were stunned when they arrived. How does a person move in waist-deep molasses? It is even possible? Horses were frozen on the ground, drowning in the thick goo and one of the first things that had to be done was to quickly dispatch them, leaving their fallen forms glued to the ground. How could the rescuers tell where a human form might be beneath the deep mass of molasses? So many died because they could not be reached in time or because they were simply overwhelmed and died of asphyxiation. Some were able to rise from the sticky mass and ride on small flotillas of flotsam and jetsam. Rescuers at the Haymarket Relief Station risked death as their boots bogged down in the mire. At the stations set up to process the injured, teams of rescuers worked tirelessly to remove the hardening molasses from breathing passages and remove the sticky clothing of the victims. Doctor and nurses soon became covered in molasses and blood.

Nothing like this had ever been experienced before. When the time came to clean the molasses, sea water became the only solvent that was plentiful and able to cut through the thick, heavy goop that covered Commercial Street. It would take weeks in the wintry weather to even begin to make a dent in the destruction. Boston Harbor went brown.

How could this have happened? The company that was responsible for the tank had a theory: anarchists. Italian anarchists were immediately labeled as the mad bombers of their day. Surely, given the disproportionate amount of discrimination that Italian Bostonians had to endure, it was easy to imagine that they might have struck back with such an act. Boston had been the hotbed for Italian anarchist activities. Why not a bomb and why not terrorism? In August of 1919, the US Industrial Alcohol Company lost two of its molasses ships, without a trace. These unexplained losses seemed to point toward the same source again: anarchists.

The Boston Molasses Disaster had ramifications that continued to run through the courts and the halls of industry. If no identifiable person or persons could be found, someone would have to bear the burden of the property damages and that had leveled Commercial Street in Boston. The US Industrial Alcohol Company would be taken to court . Valued at today’s prices, over $100 million dollars worth of wreckage was claimed.

We know from examining the records that no engineer or architect was ever consulted during the design and building of the huge tank. The tank was built quickly with an eye on spending as little as possible. Six years later the good people who lived in the North End and who lost their lives or their their homes, each received around $7000 each from the US Industrial Alcohol Company which had been found liable for all damages by the Massachusetts Superior Court. Never again would the state of Massachusetts allow such a structure to be built without state supervision and construction codes. Could such a thing ever happen again? Surely not.

But it did. A more recent molasses spill occurred in 2013 in Honolulu, Hawaii. A faulty pipe poured over 1,400 tons of the sticky mass into Honolulu Harbor. All sea life in the harbor was killed due to the de-oxygenation of the water caused by the molasses covering the entire bottom.

Sources

Puleo, Stephen, Dark Tide: The Great Molasses Flood of 1919, copyright 2004, Beacon Press, Boston.

Schworm, Peter “Nearly a century later, structural flaw in molasses tank revealed,” Boston Globe 01/14/2015